Booking travel often involves intermediaries instead of direct interaction with the service provider. Each entity in this network, from the initial search to the final payment, extracts a portion of the transaction value. While these middlemen offer market access and convenience, they introduce substantial cost layers that are rarely transparent to either the supplier or reseller, let alone the end customer.

Uncovering these hidden—or at least not completely transparent—costs is helpful for many reasons. First, no one likes to buy a pig in a poke. Second, if you know exactly where the revenue leak is, you can optimize the booking and payment process to reduce losses. Third, if you carefully evaluate all the services intermediaries provide, the higher price may seem fair, being part of a “value exchange.”

This article aims to trace this complex financial journey systematically.

Who pays for what in a distribution chain?

Each travel vertical differs in how it manages and pays for its distribution channels. In any case, each additional intermediary increases the final cost of the product (or expenses for a supplier).

Air ticket distribution through third-party channels is strictly centralized and standardized, with everything revolving around the “triple sun”—three main Global Distribution Systems (GDSs): Amadeus, Sabre, and Travelport. And it’s not going to change quickly despite the IATA initiatives—New Distribution Capability (NDC) and ONE Order—intended to reduce airlines' dependence on GDSs.

The hospitality industry, however, is much more fragmented: Every independent hotel or hotel chain seeks its own ways to fill rooms.

Here, we'll take a look at all the key distribution players, both general and specific to hotels and airlines, and break down their share of the pie.

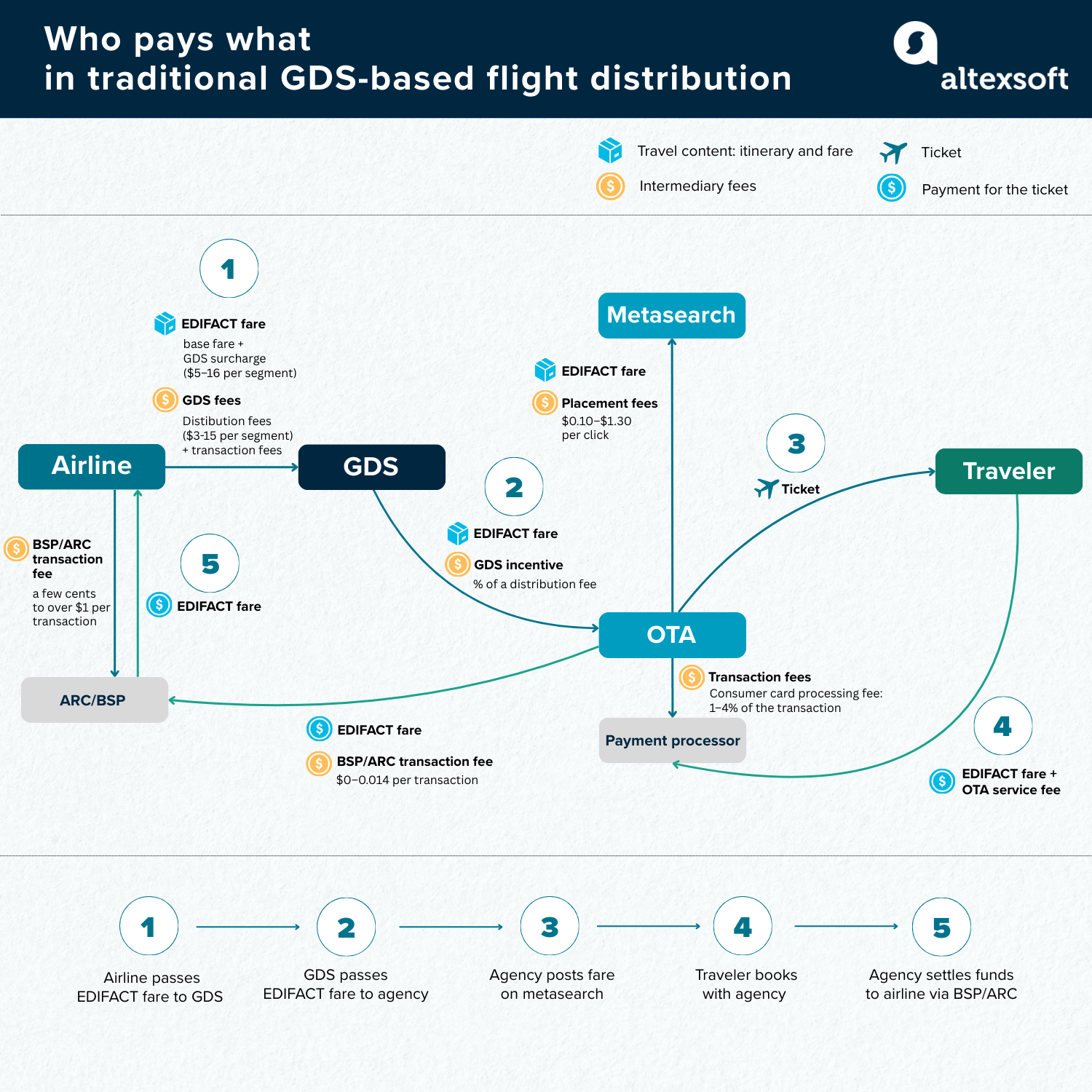

Who pays what in traditional GDS-centred flight distribution

GDS: between an airline and OTA/TMC

Global distribution systems centralize vast travel inventory, making it accessible to resellers such as traditional and online travel agencies (OTAs), travel management companies (TMCs), etc.

Although GDSs offer a wide range of travel products, from accommodations to travel insurance, they are predominantly utilized for booking flights and serve as a crucial sales channel for most full-service carriers (FSCs).

Flight booking backstage

Low-cost carriers (LCCs) have historically championed direct sales to minimize distribution costs. Still, in the 2010s, giants like Ryanair and EasyJet began selling their inventory through GDS platforms to access the lucrative business travel market (as TMCs book mainly via GDSs).

Let's evaluate all GDS-related distribution costs from the airline's perspective.

Usually, a GDS charges airlines a flat fee for each segment booked through its system. A segment is one flown passenger journey between two points (one takeoff and one landing). “It can vary from around $3 up to $15 per segment, with an average of 2.5-3 segments per ticket. It’s a lot,” says Ann Cederhall, travel technology strategist and airline retail expert.

Ticketing is usually included in the distribution fee. Still, airlines can be charged separately for other operations made via the GDS, like offering ancillary services (for example, seat selection) and canceling bookings.

“As an illustration and an example (contracts vary greatly)—say an agency books two segments, and I, as an airline, pay $4 each, $8 total, to GDS. If they’re canceled, I get most of that back, minus $0.15 per segment in cancellation fees—minus $0.30,” elaborates Ann. “If the agency rebooks, I pay $8 again, then if it’s canceled once more, that’s another $0.30 gone. With heavy churn or duplicate bookings, these fees pile up quickly. And here’s the worst case: If a booking is canceled less than 24 hours before departure, I still pay the full $8 to GDS, plus the earlier cancellation costs. So in practice, I’ve spent $8.60 for nothing.”

Altogether, GDS fees can account for up to 25 percent of ticket prices.

Is it possible to get better terms from a GDS? Yes, if you’re a large airline or if you meet specific conditions. “Full content agreements between a carrier and a GDS can bring down the costs. Also, discounts are often linked to where the airline's PSS is hosted, which you can clearly see when you compare airline surcharges for GDS booking. Typically, if an airline is hosted on Amadeus Altéa, there is a cheaper booking fee for Amadeus bookings; the same applies to Sabre-hosted airlines for Sabre bookings. Travelport doesn’t have PSS, so it’s not relevant for them. And there are airlines like United Airlines and Delta that own their PSS host, so these discounts do not apply to them,” explains Ann.

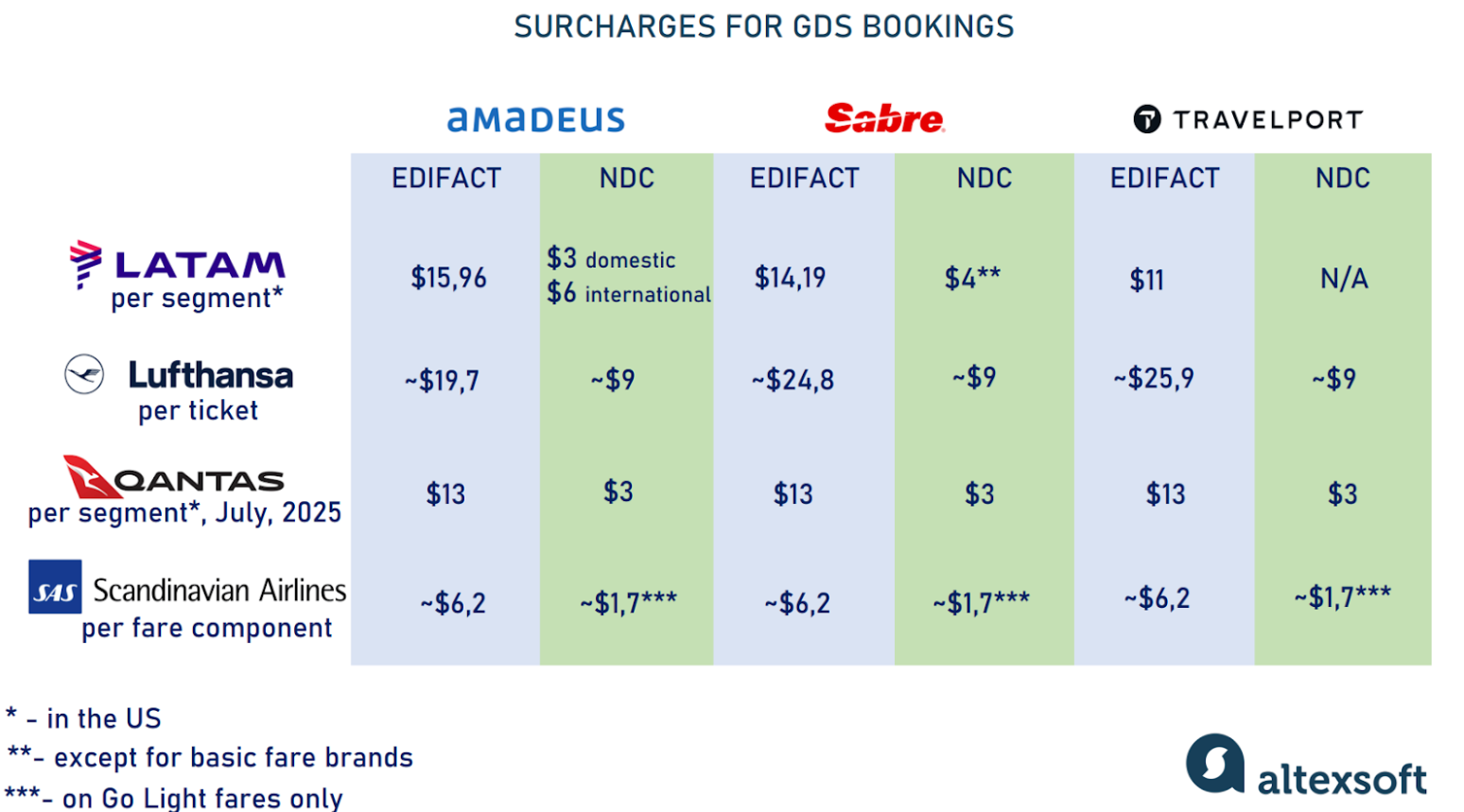

Currently, many airlines aim to reduce distribution costs by increasingly adopting NDC. To encourage NDC bookings, many major carriers add surcharges to traditional (EDIFACT) GDS reservations, which can range from $10 to $25 per segment.

Trips purchased via GDS NDC channels are also subject to surcharges. However, these fees are significantly lower (up to $6 per segment), as you can see in the table below.

Surcharges for GDS bookings

The GDS does not pay these additional costs; the end customer does. Airlines simply increase the price of tickets sold through the GDS to cover service expenses.

Now, let's look at GDS services from the perspective of OTAs/TMCs. While cooperation with Amadeus, Sabre, or Travelport requires an agency to meet certain standards(e.g., prove financial strength, be IATA/ARC certified, invest in API integrations, guarantee a high volume of bookings)—working with these giants is beneficial for resellers. GDSs pay incentives, a few dollars for each ticket sold, which are part of the fees received from airlines. In contrast, an agency pays a fee only if there is a reissue.

Flight consolidators: between an airline or GDS and OTA/TMC

Airline consolidators are technology platforms that give smaller, non-IATA agencies access to GDS content. These agencies cannot book flights directly through GDSs, so the consolidator lets them use its credentials to buy air. Service fees vary depending on the market.

Big consolidators work as wholesalers who negotiate net fares (also called bulk or private airfares) for blocks of seats that carriers consider difficult to fill. Then, consolidators mark up and resell the seats to travel agents at a price that can still be lower than the public one.

Consolidators can book seats directly from airlines or via GDS (EDIFACT or NDC channels). For EDIFACT bookings, the consolidator will get incentives from the GDS.

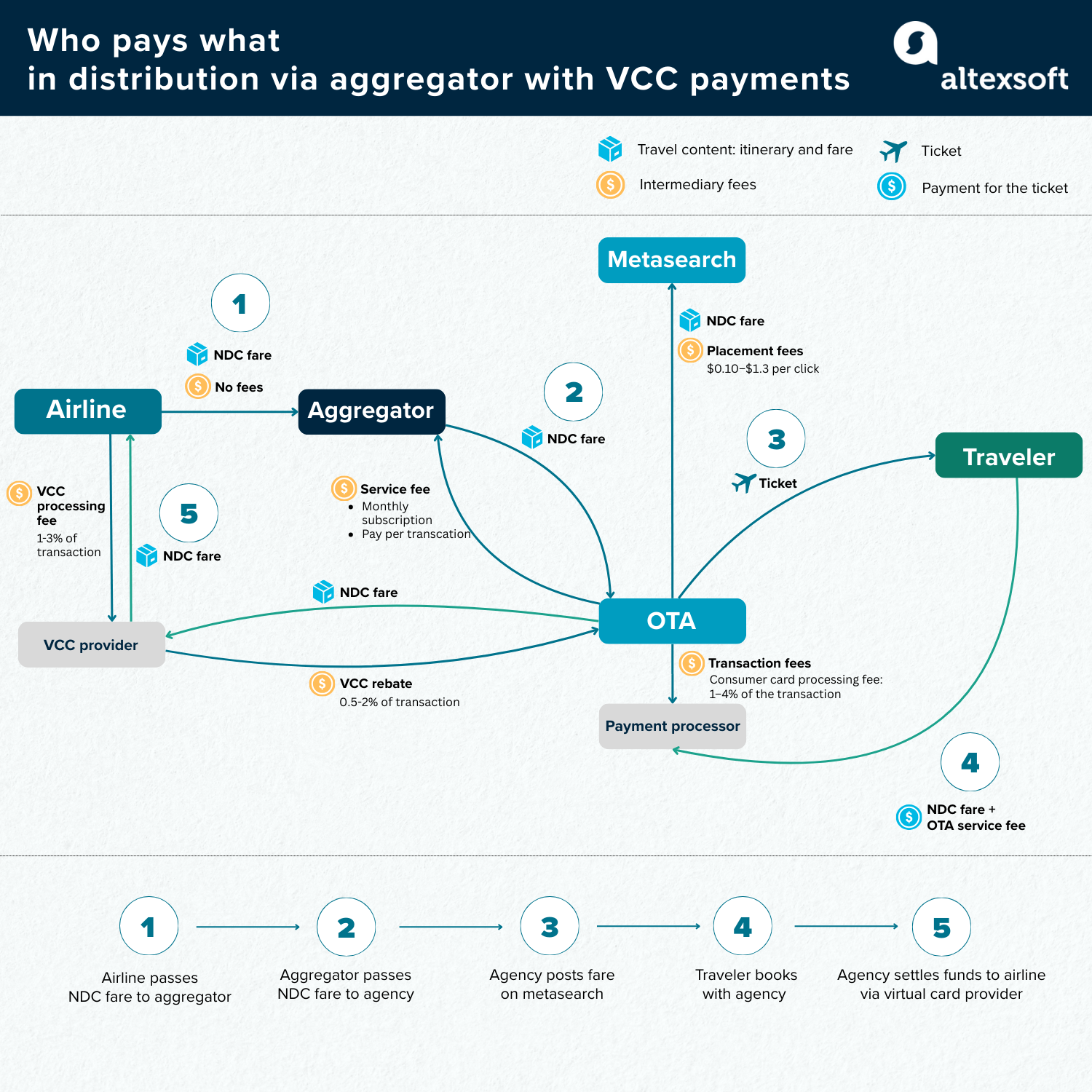

Who pays what in flight distribution via an aggregator with VCC payments

Flight aggregators: between an airline and OTA/TMC

Another possible intermediary between airlines and travel agents is flight aggregators—comparatively new players on the market. They provide a single API to search and book airline content from multiple carriers. Though the main focus of those platforms is LCC and NDC fares, they usually maintain connections with global distribution systems to offer traditional air deals too.

Unlike the GDS scenario, where distribution expenses are passed on to airlines and agencies earn incentives, aggregator services are paid by resellers. Airlines are the winners here, as they get distribution for free.

Typically, flight aggregators monetize either through paid subscriptions or on a pay-as-you-go basis—and in some cases, by blending the two. However, transparent pricing remains rare, with only a handful of providers openly disclosing their rates.

Duffel, for instance, charges $3 plus 1 percent of the total purchase price for each confirmed order, $2 for every paid ancillary, and $0.005 per search once the search-to-book ratio exceeds 1,500:1. AirGateway follows a hybrid approach: a subscription fee of roughly $108 per month, supplemented by about $1 per issued booking. DRCT, by contrast, skips subscriptions entirely, applying a fixed service fee only when a reservation is ticketed.

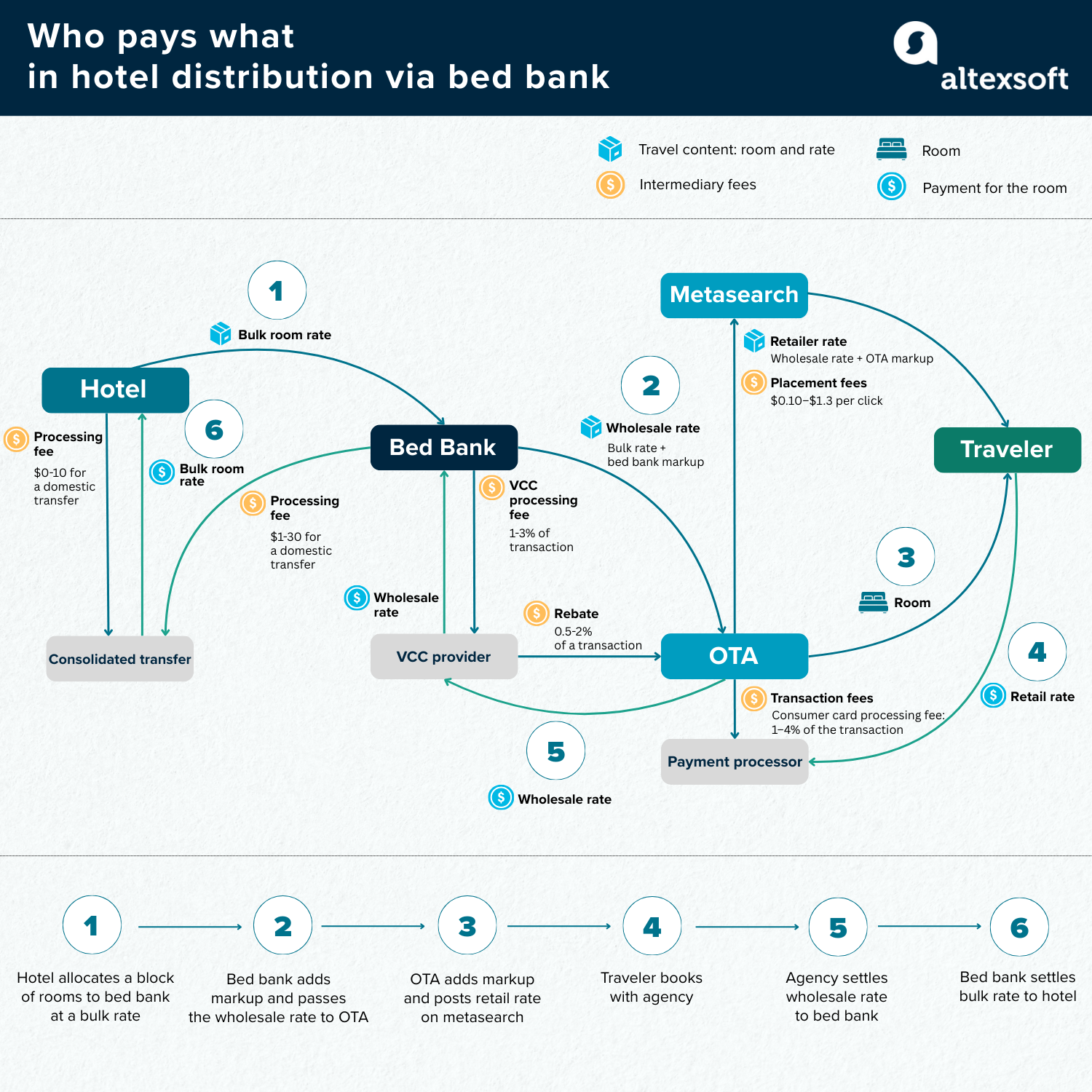

Who pays what in hotel distribution via bed bank

Bed banks: between a hotel and OTA

Wholesalers, known as bed banks, are specialized B2B platforms that negotiate a discounted price for a block of rooms on specific dates with accommodation providers and sell these rooms via their extensive network of travel retailers and intermediaries.

Bed banks make money in two main ways: adding a markup to the bulk hotel rates they buy or earning a commission from a hotel on bookings made through them. The commission-based model has now largely replaced the markup approach.

GDS: between a hotel and TMC/brick-and-mortar travel agencies

GDSs also play a significant role in hotel distribution. They allow hotel brands to reach corporate clients and leisure travel agencies, ensuring higher average daily rates and consistent demand. Smaller, independent hotels usually do not use GDSs.

Different GDSs have different fee models. There’s always a GDS fee, typically around $3 to $3.50 per transaction. But, additionally, there may also be a commission, usually 10 percent of the booking value, which the hotel pays to GDS and the latter passes it to the travel agent, who makes a reservation

Online travel agencies: between a hotel and a traveler

OTAs, with their extensive marketing budgets and dominant presence in search engine results, are the leading hotel distribution channel. While 60 percent of hotel bookings are made online, only about 20 percent are completed directly on the hotel website; OTAs handle the others.

OTAs charge substantial commissions for their services. Booking.com rates range from 10 to 25 percent, depending on the property's location, size, and cancellation policy. Expedia commission varies from 15 to 30 percent. Airbnb operates a split fee (guest 14–16.5 percent, host 3 percent) or a host-only fee (commonly 14–16 percent to host), depending on property type and integration.

There are also other ways hotels can cooperate with OTAs to fill the rooms. “OTA can say, 'Hey, give us 10 percent off for our international tourists, and we're just gonna sell only to them, not to the general public.’ It's technically not a commission; it's a discount. OTA is not taking this money; it is reflected in the end consumer price. But to the hotel, there's no difference. It drives down the net rate at the end of the day,” says Ira Vouk.

OTAs also offer an option for hotels to be ranked higher on the OTA website (and pay for this with a specific fee or a commission). “Then, in addition to the standard commission of 20-25 percent, the hotel pays extra, let's say 3 percent for special placement,” continues Ira.

Metasearch engines: between an airline/hotel or OTA and a traveler

Platforms such as Google Hotel Search, Google Flights, Trivago, Kayak, TripAdvisor, and Skyscanner collect data from travel suppliers' websites and OTA platforms to present a comprehensive selection of travel options. Google Hotel Search, TripAdvisor (originally a review platform), and Trivago focus on metasearch for hospitality, Google Flights specializes in airlines, while Kayak and Skyscanner list various types of suppliers (carriers, hotels, car rentals, and package holidays).

Metasearch engines typically operate on two models.

A pay-per-click (PPC) or cost-per-click (CPC) model, where suppliers bid for prominent placement in search results. For example, Trivago charges hotels and OTAs between $0.10 and $1.30 for each click.

“Hotels can get free placement on Google Hotels through its API, meaning they don’t pay commissions on bookings made through their website via Google. However, if a hotel wants to rank above OTA websites in the search, it needs to compete with OTAs by paying for PPC ads. This is a tough battle, as OTAs typically have much larger marketing budgets. OTAs and large hotel chains spend billions on Google advertising every year,” says Ira Vouk.

Airlines are usually not charged per click: They have enough market power to refuse to do that. Google Flights removed the CPC fee for all carriers in 2020.

Cost-per-acquisition (CPA) is a flat fee for bookings made through the platform. For example, Trivago takes 5-8 percent for hotel bookings. Hotels can choose between PPC or CPA models.

Compared to OTAs, metasearch offers accommodation providers greater control over their brand, as users are encouraged to book directly on the supplier’s website rather than through third-party platforms.

Hidden costs in payment processing

Apart from distribution middlemen, there’s another layer that often goes unnoticed: payment intermediaries. Every transaction that moves money from traveler to airline or from agency to hotel passes through a chain of players who each take their cut, and ultimately shape the final price customers see.

There's no uniformity. Travel payments fall into two very different categories: B2C, where travelers pay suppliers or intermediaries directly, and B2B, where businesses settle with each other. Each side of this ecosystem involves its players, fees, and hidden costs, creating a complex web that influences profitability throughout the industry.

Let’s explore the process in detail.

B2C payments: a traveler pays for a service

To collect money from travelers online, a merchant—whether an airline, a hotel, or an OTA—must integrate with a payment gateway or processor, which is a technology that facilitates secure electronic payments and acts as a middleman between businesses and financial institutions (card networks, banks, etc.). Among top players in this field are Stripe, PayPal, Adyen.

The merchant bears the cost of payment processing, which will depend on the service fees charged by the payment gateway, the payment method used (credit card, digital wallet, etc.), whether it’s a local or international transaction, and other factors. Because of many variables, these expenses are not always transparent.

“Processor fees are where variability and ‘hidden' costs most often arise,” says Tony Vardiman, Head of Global Payments at Cloudbeds, a hospitality management platform.

Over time, processors have developed complex pricing structures, using terminology and line items that can be difficult for merchants to interpret. This lack of clarity often creates the perception of 'hidden' fees, even if the charges are documented

“Complex pricing structures developed due to the growing complexity of the payments ecosystem,” notes Paul van Alfen, Managing Director at Up in the Air, a consultancy firm specializing in travel payment strategy.

Here are some examples of such hidden costs:

- Discount rate. Despite its name, this term refers to the actual processing rate that merchants pay, not a discount in the traditional sense.

- Statement or monthly fees. Recurring charges for account management, such as those for generating reports or maintaining accounts.

- PCI compliance fees. These fees are sometimes charged to help merchants meet the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). However, the scope and justification for these fees can vary significantly.

- Miscellaneous surcharges. These include additional costs like gateway fees, batch processing fees, or network access charges.

While each fee may seem minor, they can accumulate and complicate the process of accurately determining the true cost of payment acceptance.

“From an analytical perspective, the 'hidden' nature of these payments lies less in their existence and more in their presentation–fees are fragmented across multiple categories and statements, making it difficult for travel businesses to fully understand their effective rate without a detailed audit,” adds Tony.

It’s worth noting that the pricelists of providers like Stripe or Adyen already include method-specific fees, along with any gateway and processor charges.

The final cost of payment acceptance is also largely dictated by the method used—credit or debit card, digital wallet (like PayPal or Apple Pay), Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) options such as Klarna, or regional solutions like iDEAL or Blik.

“70-80 percent of direct payments to travel agencies are made by cards, especially in more credit-based countries, like the US and UK. Visa and Mastercard combined are typically two-thirds of that. But it differs between leisure and corporate customers: The latter typically use corporate cards like American Express, UATP, and others,” says Paul van Alfen.

So, what expenses are there? Card-related costs consist of two components:

- card network fees established by card networks like Visa or Mastercard; and

- interchange fees paid to the cardholder’s bank to cover fraud and chargeback risks, as well as processing costs and cardholder incentives. In travel, which is considered a high-risk industry, these fees are higher than, for instance, in retail.

Some LCCs make passengers pay for card transactions to protect margins. For instance, Jetstar clearly states that credit card payments incur a fee (from 0.37 to 1.75 percent), whereas PayID bank transfers or voucher/gift cards are accepted for free.

In Europe, consumer cards cannot be surcharged, but corporate cards can be.

On cards not capped by European regulation, suppliers are allowed to surcharge up to the actual amount they have to pay for it

So, card-related costs are circumvented or passed on whenever possible. What about other payment methods?

“Processors typically charge the same rates for most mobile wallets like PayPal as they would for standard credit card transactions. But BNPL providers generally charge higher transaction fees – often up to 250 basis points (or 2.5 percent of volume) above traditional card rates," says Tony Vardiman. "The incremental revenue from increased bookings and higher spend may offset the additional fees – but this needs to be carefully modeled to ensure profitability.”

Some payment methods (like A2A and mobile-based money transfers) don’t leverage card rails and, therefore, don’t involve card networks and associated fees.

B2B payments: an intermediary pays suppliers

B2B transactions in travel include commission payments (such as those from hotels to bed banks or OTAs), payments between partner airlines, and various other financial interactions. In this section, we will focus on one example: the payouts resellers make to travel suppliers.

After the agency collects money from travelers, it faces the task of disbursing funds to suppliers — airlines, hotels, car rental companies, and other service providers. The payout methods vary by sector and geography, but each carries its own costs and hidden frictions.

BSP and ARC settlements. Flights sold through GDSs are typically settled via IATA’s Billing and Settlement Plan (BSP) or Airline Reporting Corporation (ARC) in the US. These clearinghouses allow agents to make consolidated payments for all tickets they purchase during a two-week reporting cycle.

For carriers, BSP and ARC are essential for smooth and efficient settlement. “BSP cash is very robust and pretty much global,” says Paul van Alfen.

But this convenience comes at a price. AltexSoft has interviewed several parties and understands that the cost can vary from a few cents to over a dollar per transaction.

The cost for BSP is based on airline volume, and you pay per transaction. Note that a ticket, an EMD, an ACM, an ADM, and a VOID are all transactions. In addition, you pay for the access

BSP/ARC is also fairly pricey for travel agents. To join the platform, the travel company must provide a bond guarantee ($30,000– $50,000, depending on the agency's size).

While BSP has no transaction fee for agencies, ARC does. The organization classifies all agencies according to the number of transactions per quarter: tier 1 has 1,000–2,224,999 transactions, tier 3 has 6,000,000 or more, and tier 2 has everything in between. Accordingly, tier 1 pays $0.014 per transaction, tier 2 pays $0.013, and tier 3 pays $0.012. If there are fewer than 1,000 transactions, there's no charge.

Overall, it's not that much. However, the agencies paying via BSP/ARC incur indirect costs.

“For instance, there is no protection,” says Paul. “If the travel agency has been billed for tickets issued in January, and the airline goes bankrupt in April, the travel agency still has a responsibility to refund the customer, but they can't deduct that from what they paid to the airline. They have to wait, and it can take years to get the money back. Especially during the pandemic, many travel agencies got cold feet about that because many flights were canceled, and refunds were pending. So they looked at alternatives, like virtual cards.”

Virtual credit cards. In B2B transactions, a virtual card (VCC) is a unique 15- or 16-digit number tied to an actual card account and generated to pay a set amount in a chosen currency to a specific recipient. The main advantage of a virtual over a physical card is greater security and spending control, as it can be issued with specific limits for a single purchase, a set period, or selected suppliers.

As always with cards, the recipient pays a transaction fee. But there is a caveat. “Commercial card products — whether virtual or physical — are more expensive than consumer cards because their interchange rate is higher,” says Mark Anthony Spiteri, SVP and Global Head of the Card Business at Nium, a real-time cross-border payments company. “Also, within commercial cards, you have different interchange levels. Some might be 265 basis points, while others might be 50 basis points. Sometimes you get into what's called blended rates. The acquirer says, 'I’m going to give you a blended charge of two or three percent,' which simplifies pricing but more often than not obscures cheaper underlying rates for certain mixes.”

So, at first sight, VCCs don’t appear to work in favor of suppliers (airlines, hotels, or car rental companies). But the latter benefit anyway. According to Paul, “Especially airlines see cashflow impact, protection against agency default, richer data, and a positive impact on sales. It's a value exchange!”

For agencies, VCCs are certainly advantageous. The issuer pays an agency a rebate, essentially a portion of the supplier's fee. Say, if the interchange fee is about 2.5 to 3 percent, the rebate may be 0.5–2 percent. And there’s another advantage for an intermediary—protection in case of supplier bankruptcy. The credit card acquirer will have to take the hit and refund the consumers.

For these reasons, agencies are eager to pay with virtual cards, yet airlines often refuse them. What’s the way forward?

“It shouldn’t be black and white. An airline and an OTA can agree, ‘We’re not going to use the 200 basis points card, but only the 100 basis points card.’ That’s a nice medium where both parties are happy. Some airlines go further and require that agencies use only specific interchange-level products for particular routes or fare classes,” says Mark Anthony.

“If you are a carrier with away markets where you don't have brand recognition, you should incentivize the travel agency by allowing them to use the 200 to sell that flight,” adds Paul van Alfen. “But for flights that are always fully booked with corporate travelers, you shouldn't allow agencies to use it at all. I think airlines can use this form of payment better to optimize distribution.”

Besides VCCs and BSP/ARC, other payment methods are commonly used for payout.

Checks. In some markets, particularly North America, paper checks are still used in supplier settlement. On the surface, they appear low-cost — banks charge little to process them — but the true expense lies in inefficiency. Checks can take a week or more to clear, impose administrative handling costs, and create working-capital delays for suppliers waiting for funds.

Bank transfers. These are another comparatively low-cost method. The bank sending the payment usually charges a flat fee to initiate a transfer. Domestic transfers over local low-cost networks (like ACH in the US or SEPA in Europe) often have small transactional fees. For example, Bank of America charges $1-$30 for a domestic wire, depending on the type (a three-business-day transfer is the cheapest), with a limit of $5000 per transaction.

The receiving bank may also levy a fee to credit the incoming funds. Bank of America charges $15 for inbound transfers, no matter which country it's from.

In many other regions (EU, UK, etc.), standard domestic transfers have no incoming fee. In contrast, an incoming international SWIFT transfer might incur a fee ($10–$30 or equivalent).

Also, for international payments via the SWIFT network, funds often pass through one or more intermediary banks. Each may deduct a fee en route (typically $10–$20 per intermediary).

It’s worth noting that international wire costs are small compared to cross-border card transaction costs, which we’ll discuss in the next section.

Cross-border and currency costs in card transactions

Because travel is inherently global, cross-border payments are often unavoidable. Whenever funds move between currencies or across jurisdictions, additional costs creep in, whether it’s a consumer or corporate card.

The cross-border fees are probably the largest chunk of the card transactions. The interchange plus network costs will typically be between 3 and 4 percent.

“The cross-border fees are probably the largest chunk of the card transactions,“ says Mark Anthony Spiteri. “The interchange plus network costs will typically be between 3 and 4 percent.”

Network and issuer fees. When a cardholder's issuing bank and merchant's acquiring bank are in different countries or regions, card networks apply cross-border assessment fees on the accepting side. “Issuers may also add foreign transaction surcharges, which can increase the effective cost of acceptance by 30–100 basis points,” says Tony Vardiman.

Since airline margins are extremely low, carriers sometimes avoid these costs by refusing to accept international cards or even taking more radical measures.

“In Asia-Pacific, airlines typically received most of their transactions via local payment methods, where the cost was close to zero, less than 0.5 percent. Then, travel agents started using cross-border cards, and suddenly their cost went close to 5 percent. So, how do you justify going from close to zero to 5 percent? The carriers’ strategy was, ‘We’re not going to accept commercial cards at all," says Mark Anthony.

Foreign exchange (FX) leakage. It occurs due to unfavorable exchange rates and unnecessary currency conversions in cross-border payment flows. For example, if a Canadian tour operator pays a Mexican hotel, and the payment is forced through USD, it will result in a "double conversion" (first CAD to USD, then USD to Mexican pesos).

Dynamic currency conversion (DCC). It’s a service offered at ATMs or points of sale in foreign countries, where the merchant's bank or the ATM provider converts the transaction price into the cardholder's home currency. And it’s often part of a hotel payment because typically guests pay at checkout.

While presented as a convenience, DCC almost invariably results in higher costs for the consumer since the ATM provider or the merchant's bank sets the exchange rate, which includes a markup or additional fees. Although the customer bears the direct costs, the hotel can be exposed to indirect losses if DCC is not appropriately managed: “Hotels typically have limited visibility into DCC fees and markups, which can impact both booking conversion and guest satisfaction. The remedy is twofold: Negotiate the exchange-rate terms with your payment processor - and present payment options clearly so guests can make an informed choice," says Tony Vardiman.

Other indirect costs of cross-border card transactions include longer settlement times, which can strain working capital for smaller hotels that rely on timely cash flow, especially during peak seasons. Reconciliation is also more complex, as multicurrency transactions and FX markups make accounting time-consuming and error-prone. On top of that, opaque fee structures mean hotels often see only net deposits, with little visibility into the actual breakdown of costs. This lack of transparency prevents them from benchmarking expenses or optimizing how they handle international payments.

Is there a way for the travel business to mitigate these impacts?

“Using local cards instead of cross-border cards can help. Airlines, especially international ones, can use local acquiring routes rather than processing everything through international routes,” says Mark Anthony Spiteri. “For instance, if you're booking a flight from Malta with Turkish Airlines, they may acquire the transaction in Malta because the card is issued there. This reduces cross-border fees. Similarly, OTAs are opening offices in multiple countries to work with local payment providers, lowering costs.”

According to Tony Vardiman, “Letting guests pay in their own currency at transparent exchange rates can improve conversion while reducing reliance on costly DCC services. Larger hotel groups and OTAs can also mitigate FX exposure through treasury tools—special software that manages or hedges currency risk. Hotels that accept payments in multiple currencies benefit from maintaining accounts in their primary receipt currencies. Route each payment to its like-currency account. For example, deposit GBP receipts into a GBP account and EUR receipts into a EUR account. This helps to avoid forced conversions on deposit and reduces FX spreads and fees.”

What else to consider: general strategies for transparency and cost optimization

Tackling hidden costs in travel payments isn’t just about spotting individual fees—it requires a broader approach to transparency and efficiency, as well as an understanding of the value you're paying for. While no single solution eliminates every layer of complexity, companies can adopt strategies that improve visibility, streamline processes, and reduce unnecessary spending along the payment chain.

Demand transparency

All parties involved should be interested in sharing as clear information as possible about applied fees.

“I believe transparency should be the standard—not the exception—in payments. When banks and payment platforms avoid jargon and clearly separate fees, hotels can finally understand their true cost of acceptance,” says Tony.

Michael Duffy, Product and Innovation VP at Grasp, a technology platform for corporate travel management, emphasizes that transparency is extremely important for corporate clients. “Take VAT, for instance. In some regions, corporates can reclaim that tax, but they need to see it in the reports. The same goes for foreign exchange. If there’s a large markup and it isn’t visible, clients may just assume that’s the cost of doing business. But if they could actually see that markup, they might realize, 'Hey, I’m paying too much for FX,' and then negotiate with their supplier or look for other options. At the end of the day, it’s up to the corporate client to demand that transparency — because otherwise, it won’t happen.”

Negotiate better terms

In a word, negotiate! Discuss, make concessions, get a little less profit — it's better than not getting any at all.

“There’s been a trend where travel agents, resellers, and intermediaries have discussions with suppliers to agree on cost structures. This enables negotiation, ensuring both parties benefit. Unfortunately, this isn’t widespread, and players in the industry need to work together to find solutions that work for everyone,” says Mark Anthony Spiteri.

Abandon legacy systems

Automate manual processes for handling payments and reconciliation.

Inefficiency is the major source of hidden payment costs in travel. There are many manual processes. TMCs, OTAs, and hotels rely heavily on legacy technology and processes, and the systems don't communicate well. So often, a human has to get involved to process or reconcile the payment. It's all the labor cost

“Even at a modest scale, finance staff might spend 20–40 percent of their time reconciling fragmented payment reports. For a small hotel with 1–2 accounting staff, this could represent $15K–$30K annually in labor costs,” elaborates Tony.

Use payment orchestration

These are another layer between acquiring banks and local payment service providers (PSPs). Payment orchestrators have a sophisticated rules engine that helps route transactions through the system to, for instance, the most cost-effective or most successful route from an acceptance rate perspective. The gateway might do retries or flow transactions through it and also invoke fraud screening or secure logic.

orchestrator would handle the whole logic of managing and processing the transactions. Then they might connect directly to a bank or hand it over to a payment gateway for further handling. You add a layer, but the idea is that by streamlining the process and making it more effective, you reduce the overall cost of accepting payments by leveraging that technology

The truth is, there’s no magic wand to use to erase complexity. Yet companies that prioritize transparency are better positioned to optimize costs and deliver smoother experiences for travelers and partners alike. In other words, if hidden payments are the turbulence, transparency and cost optimization are the seatbelts that keep everyone safely seated.

Olga is a tech journalist at AltexSoft, specializing in travel technologies. With over 25 years of experience in journalism, she began her career writing travel articles for glossy magazines before advancing to editor-in-chief of a specialized media outlet focused on science and travel. Her diverse background also includes roles as a QA specialist and tech writer.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.