Ancillary revenue is on a major upswing. In 2024, airlines earned roughly $150 billion from non-ticket sales — a $32 billion jump over the previous year. This growing stream has become even more vital amid fare declines of 4 percent in business class and 3 percent in economy. With weaker than expected demand, airlines have had to cut prices to keep planes full. But what used to be “add-ons” now play a key role in keeping profits steady.

In this article, we’ll look at the key types of airline extras, how they boost revenue, and how airlines are finding new ways to monetize the travel experience beyond the ticket price.

Airline ancillary revenue overview

What is ancillary revenue?

Ancillary revenue refers to the money a company earns from goods and services beyond its main offering. In aviation, it includes everything passengers purchase directly or as part of the travel experience outside the ticket price. This broad category covers

- a la carte ancillaries — individual add-ons that passengers purchase separately from the fare, such as checked baggage, seat selection, or in-flight WiFi;

- frequent flyer programs (FFPs) — the sale of miles or points to partners like hotel brands, car rental companies, retailers, and co-branded credit-card issuers;

- third-party ancillaries — services provided by partners, including hotel bookings, car rentals, and airport transfers; and

- promotions and advertising — placements across an airline’s website, mobile app, in-flight bulletins, overhead bins, and other touchpoints.

For most major legacy carriers, the bulk of ancillary revenue stems from their FFP partnerships with co-branded credit cards. We have a dedicated article explaining how airline loyalty programs generate consistent cash flow, even during downturns.

In this post, we’ll focus on passenger services not included in the fare — particularly the a la carte segment, which drives revenue growth for many airlines, along with third-party travel products.

The brief history of the unhidden treasure

For decades, airlines bundled all services into the ticket price. This wasn’t just a business choice but a technical necessity: The core platforms that powered flight sales — passenger service systems (PSSs) and global distribution systems (GDSs) — weren’t built to handle the complexity of multiple optional add-ons.

How traditional airline distribution works

The real turning point came in the early 2000s with the rise of low-cost carriers (LCCs) such as Ryanair and easyJet in Europe, and Southwest in the US. These disruptors embraced newer technologies and leaned on direct distribution, allowing them to bypass GDS limitations. Selling through their own websites, they offered ultra-low base fares — and charged separately for everything else.

Ryanair was among the first to push the model to its limits. It introduced fees for checked baggage in 2006, followed by charges for priority boarding and check-in. The airline also pioneered fees for seat selection and hand luggage. Still, Ryanair and the like deserve credit — they opened the skies to millions of travelers who previously couldn’t afford to fly.

The unbundling strategy turned out to be a gold mine. Soon, full-service carriers (FSCs) followed suit, driven by the oil shock of 2007-2008 and a surge in fuel prices. In June 2008, American Airlines became the first FSC in the US to charge for a first checked bag on domestic flights, breaking from the long-standing practice of including two checked bags with every fare.

The backlash was instant and fierce. Passengers called the move “stupid,” “insane,” “ridiculous,” and “greedy.” Many vowed never to fly AA again, to take the train, or switch to low-cost rivals like JetBlue — some even wished the airline would go bankrupt.

Yet by the end of 2008, American Airlines reported around $278 million in baggage fee revenue, with earnings tripling in the second half of the year after the new charge took effect. Other major US carriers — United and Delta — quickly joined what critics had dubbed AA’s “greedy initiative.”

LCC vs FSC: what’s the difference?

However, the baggage revolution didn’t immediately transform airline retailing. Traditional carriers that relied on GDS infrastructure still faced technical barriers that made it difficult — if not impossible — to distribute extras through third-party platforms.

To break free from the constraints of legacy systems, IATA launched the New Distribution Capability (NDC) in 2012 — an industry-wide initiative to bring airline sales into the digital age and allow richer, more flexible offers.

How NDC boosts airline retailing

Yet, it would take more than a decade for NDC to move from pilot projects and cautious trials to real-world adoption, as agencies, GDSs, and tech providers finally began supporting NDC channels at scale.

Read our articles on NDC adoption challenges for resellers and NDC adoption challenges for airlines to understand why it takes players so long to move to new standards.

The rollout of NDC and the rise of modern order management platforms have brought Amazon-style retailing to aviation. As major carriers adapt new technologies and rethink their product strategies while LCCs continue to expand, ancillary services have finally become a core driver of airline profitability.

Current state of things and top performers

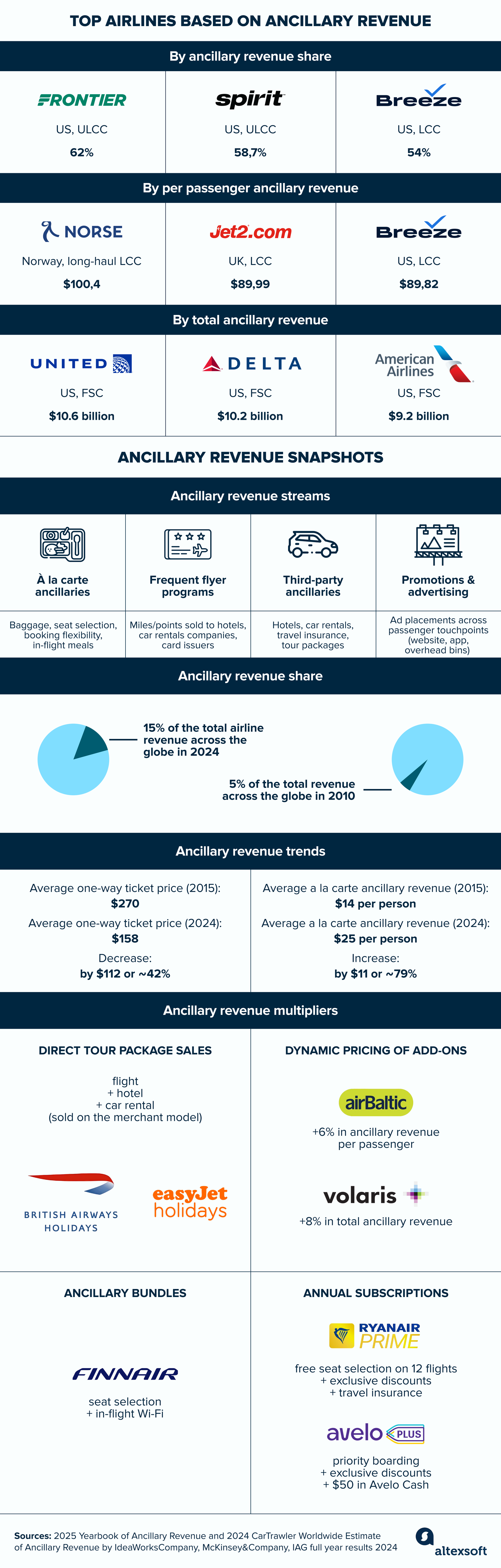

Although base fares remain the foundation of airline budgets, ancillary services already contribute a crucial 15 percent of total revenue worldwide — a sharp increase from just 5 percent in 2010. Depending on the carrier, that share can range from a modest fraction to more than half of overall earnings.

Airlines with the largest share of ancillaries in total revenue

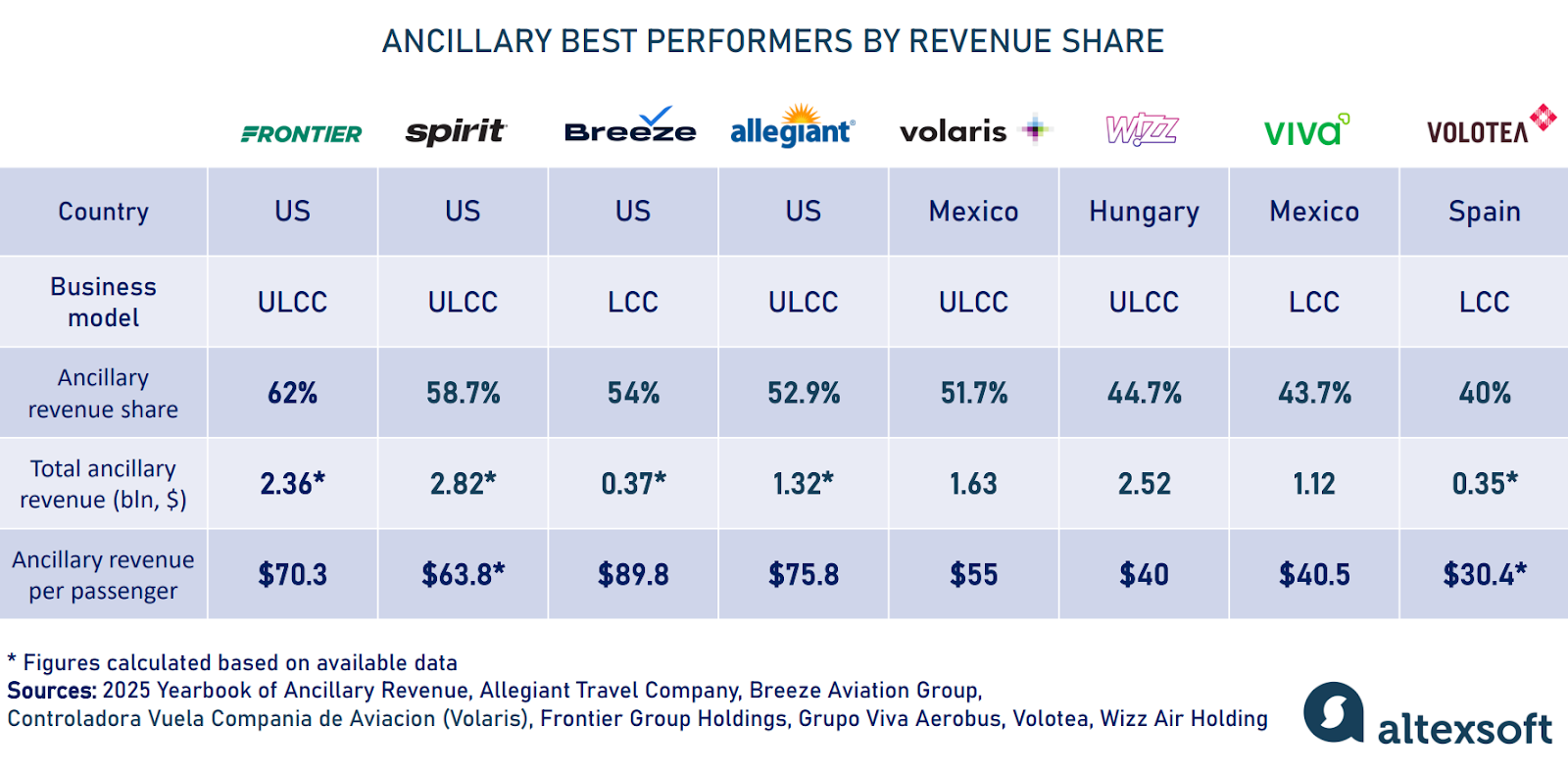

In 2024, five airlines passed the 50-percent mark, generating more cash from extras than from tickets. With the exception of Breeze Airways, a low-cost airline, all are ultra-low-cost carriers (ULCCs) — and while Volaris is based in Mexico, the rest are headquartered in the United States.

- Frontier Airlines (US, ULCC) — 62 percent

- Spirit (US, ULCC) — 58,7 percent

- Breeze Airways (US, LCC) — 54 percent

- Allegiant Air (US, ULCC) — 52,9 percent

- Volaris (Mexico, ULCC) — 51,7 percent

Despite Spirit Airlines being among the top performers, this success wasn't enough to shield it from financial losses. In 2025, the budget carrier filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection for the second time, highlighting that extras couldn’t fully offset the broader economic pressures and operational hurdles.

In per-passenger ancillary revenue, two European LCCs — Norse Atlantic Airways and Jet2.com — lead the pack.

- Norse Atlantic Airways (Norway, long-haul LCC) — $100,4 per passenger

- Jet2.com (UK, LCC) — $89,99 per passenger

- Breeze Airways (US, LCC) — $89,82 per passenger

- Allegiant Air (US, ULCC) — $75,83 per passenger

- Frontier Airlines (US, ULCC) — $70,29 per passenger

While low-cost carriers excel in earnings per passenger and share of income from add-ons, full-service carriers — especially major US airlines — dominate in total ancillary revenue. The top three performers are United Airlines with $10.6 billion, Delta Air Lines with $10.2 billion, and American Airlines with $9.2 billion. Yet, these figures represent a relatively modest portion of their overall revenue — 18.6 percent for United, 17 percent for American, and 16.8 percent for Delta.

Now, let’s take a closer look at the services that make up the most visible and fastest-growing layer of ancillary revenue.

A la carte ancillaries

A la carte ancillaries remain the lifeblood of the LCC business model. However, they have also become a key revenue source for full-service carriers, which increasingly promote the lowest basic economy fares to attract price-sensitive passengers while generating profits from those willing to pay for add-ons.

As a result, over the past decade, the average one-way ticket price has dropped by $112, from $270 in 2015 to $158 in 2024. At the same time, passenger spending on extras has risen to $25 per person, an increase of $11 compared to ten years ago. Interestingly, about 45 percent of travelers purchase only the fare, while the remaining 55 percent pay for additional comfort and convenience, helping to offset the low-cost segment.

Baggage allowance — the heavyweight of the ancillary world

LCCs are known for charging passengers for nearly everything they take along on the journey — apart from an individual item that must fit under the seat. Most FSCs, by contrast, let travelers bring a standard carry-on bag to be stored in the overhead bin at no extra cost. Yet the gap between these models has been steadily narrowing.

Baggage allowance policies and fees applied to their lowest fares on domestic routes.

Since American Airlines pioneered the first checked bag fee in 2008, most traditional carriers throughout Europe, North America, and Latin America have embraced the approach for economy class tickets. In 2024, US airlines set a new record: Thirteen carriers — spanning both FSCs and LCCs — collectively earned $7.27 billion from checked baggage fees. American, Delta, and United each surpassed the $1-billion mark. A year later, even Southwest Airlines — the last major U.S. carrier to hold out —introduced the baggage fee for all but its elite frequent flyers. After half a century, the airline retired its iconic “Bags Fly Free” policy under mounting investor pressure.

Many legacy airlines in Europe and the US have gone a step further, imposing fees on carry-on bags for their lowest-priced basic fares. Meanwhile, in the Asia-Pacific and African markets, traditional airlines largely continue to include the first checked bag — not to mention hand luggage — for all fare types.

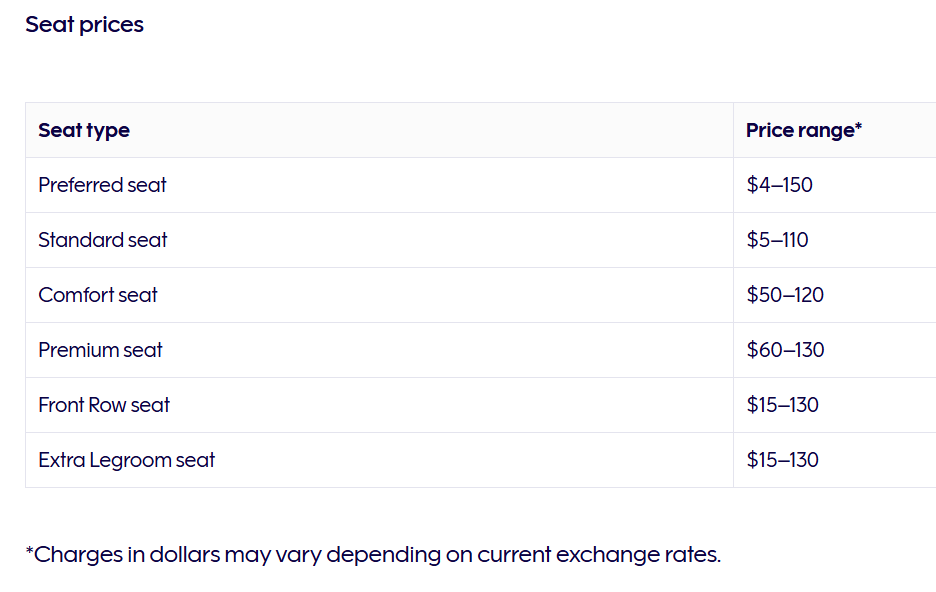

Seat selection — the second-best money maker

While baggage fees have long been the largest component of a la carte ancillary revenue, they come with hefty operational costs—think check-in labor, ground equipment upkeep, and higher fuel consumption from the extra weight.

By contrast, fees for seating options like aisle, window, and extra legroom, or earlier/priority boarding incur minimal costs. After all, the physical seat exists whether passengers pay a premium for it or get it assigned for free at the gate. As a result, nearly every dollar generated by the seat map goes straight to an airline's bottom line.

Seat selection fees by Finnair. Source: Finnair

In a significant shift, United Airlines collected $1.3 billion from seat selection fees in 2023, exceeding its baggage fee revenue of $1.2 billion for the same period for the first time. This highlights the airline industry's growing emphasis on monetizing cabin space. For passengers, the trend could mean paying extra for minimal comfort, as seen, for example, with WestJet. Canada’s second-largest carrier has introduced an interior with fixed seats, claiming the design will help passengers preserve personal space. At the same time, it also offers the option to buy a reclining seat — but in a much more expensive premium cabin.

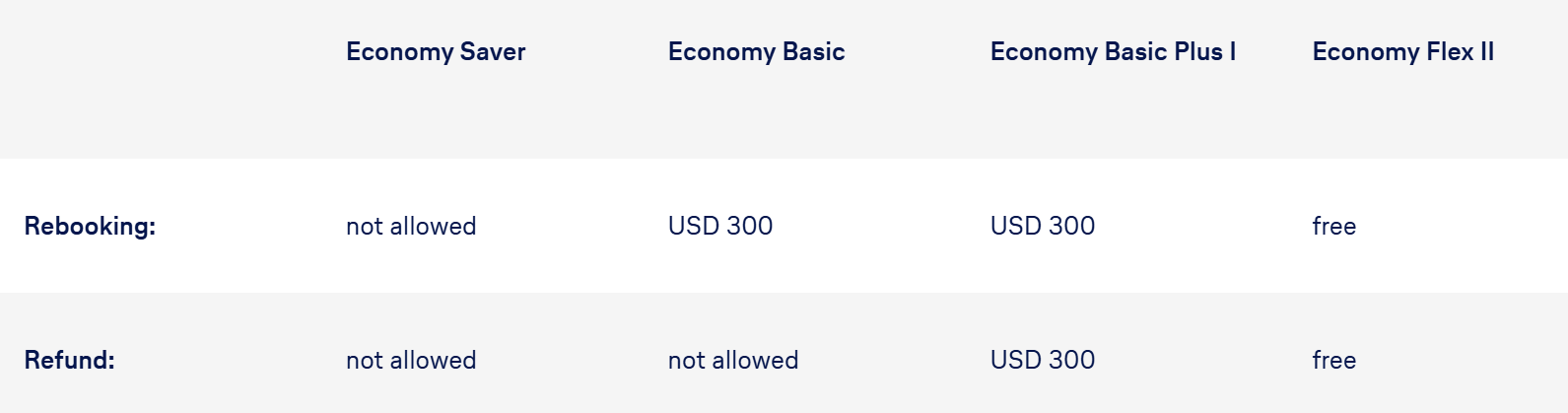

Changes and cancellations — penalties rebranded as perks

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, change and cancellation fees were a significant revenue stream for airlines. In 2019, US carriers alone raked in $2.8 billion from charges, hitting $200 for a single domestic flight.

When the coronavirus brought travel to a halt, many airlines ditched penalties to retain customer loyalty during uncertain times. "Change fees? Never again! We’ve crossed that bridge!" Delta declared after the pandemic subsided. But did airlines truly forgo lucrative charges in the name of customer goodwill? Not exactly. Instead, they bundled this money into fares that offer more flexibility, while the cheapest economy tickets often can’t be changed or canceled, at least for free.

For example, Delta allows passengers to get a refund for a basic fare, but they must forfeit between $99 and $199. Air France-KLM offers free changes and partial refunds with the Flex fare option, available in all cabin classes. Otherwise, the airline charges $80 to $345, depending on the route and class of service. Lufthansa doesn’t allow rebooking or cancellations for the cheapest tickets, but higher economy tiers allow changes and refunds for a fee of $300. Once upgraded to Economy Flex, changes and refunds are free.

Lufthansa’s change and cancellation policy across the economy class. Source: Lufthansa

In many cases, money for cancellations is issued as a flight credit or voucher, which can only be used to book future travel with the same airline and expires in a year. To get a refund to the original payment method—say, a credit card—passengers again need to buy a higher-tier fare, upgrade their current ticket, or purchase a special add-on.

So, while passengers once faced fines when their travel plans changed, they now pay extra for flexibility—often each time they fly.

In-flight ancillaries — keeping passengers full and connected

Airlines are shifting beyond just pre-flight options like seat selection and turning the in-flight experience itself into a major revenue driver. What were once free or non-existent services—think Wi-Fi, meals, and shopping—are now integral to the modern airline’s offerings at 35,000 feet.

In-flight meals, snacks, and beverages. The in-flight catering market reached $19.6 billion in 2024 and is expected to soar to around $35 billion by 2034. Full-service carriers are leading the charge, covering 73 percent of the market, with economy class accounting for the largest share at 62 percent, thanks to the high volume of passengers.

Airlines are increasingly rolling out pre-order systems, enabling passengers to select their meals in advance. This approach not only helps reduce food waste but also expands meal options, offering healthier choices like vegetarian and gluten-free dishes, along with destination-inspired meals.

In-flight shopping. In the past, selling duty-free products during flights was the sole alternative revenue stream available to airlines. Now, it’s the second-largest in-flight segment, valued at $12.3 billion in 2024 and projected to grow to $25.7 billion by 2033. The US plays the major role here, thanks to its vast network of domestic and international flights, while the Asia Pacific region is emerging as the fastest-growing market.

Luxury goods and duty-free items drive much of the revenue, reflecting passengers' interest in exclusive products while flying. Looking ahead, the market’s growth will be fueled by technological innovations — think mobile payment solutions and better flight connectivity — which will shift in-flight shopping from traditional preloaded catalogs to interactive digital platforms.

In-flight Wi-Fi. Since Lufthansa pioneered onboard connectivity in 2003, it has evolved from novelty to universal expectation and a growing market, which hit $1.79 billion in 2024 and is expected to be at $2.99 billion by the early 2030s. Maybe it’s not that much compared to mature revenue streams (the in-flight catering market is ten times larger than Wi-Fi), but in terms of customer loyalty, it’s becoming a crucial differentiator.

Carriers usually provide complimentary or discounted Internet to frequent flyers and passengers in first or business class. Others can use basic messaging at a low cost (or for free) while paying a premium for high-speed access suitable for streaming and video conferencing. As of now, the largest share of revenue (48 percent) belongs to standard Wi-Fi, which is sufficient for browsing the web and checking emails, but not for watching Netflix.

In-flight Wi-Fi isn’t everywhere just yet. While many major airlines, particularly in the US, which leads the segment, offer it at least on long-haul or high-demand routes, smaller carriers and LCCs are still catching up—providing the Internet on select flights or not at all.

Only a few FSCs have equipped some of their fleet with high-speed connectivity, including United, Hawaiian Airlines, Air France, Qatar Airways, Air New Zealand, Air Canada, Etihad, and Malaysia Airlines. But here's the exciting part: Viasat, a global communications company powering Wi-Fi for over 4,000 airlines worldwide, predicts that in just three years, the majority of aircraft will deliver "full, fast, and free" connectivity, reaching a billion passengers annually.

Third-party ancillaries

A flight is often just one part of a traveler’s journey. By connecting passengers with hotels, car rentals, transfers, and other service providers, airlines have turned their websites into one-stop shops for every stage of the trip. Besides convenience, customers also benefit from exclusive discounts and perks negotiated by carriers.

Commission-based revenue

Today, nearly every major airline — from full-service to ultra-low-cost operators — collaborates with other travel suppliers, acting as an agent and earning commission on sales made via its website. These rates depend on the partnership's terms, transaction volumes, and supplier type, starting at 5 percent with car rentals and averaging around 24 percent when reselling insurance policies.

Ryanair and Alaska Airlines, for instance, team up with Expedia Group for hotel and vacation rental bookings. Many maintain direct agreements with car rental brands like Hertz, SIXT, Europcar, or Avis, or collaborate with aggregators such as CarTrawler and Rentalcars.com, part of Booking Holdings.

Ground transportation has also joined the mix. Heathrow Express, the high-frequency rail link between Heathrow Airport and central London, first partnered with Aer Lingus in 2013 and has since added carriers like Cathay Pacific and China Airlines.

Another common collaboration is with well-established travel insurance providers. One of the most prominent players in this space is Allianz Group, which partners with numerous airlines worldwide. Depending on the region, their insurance plans may include trip cancellation, travel protection, emergency medical care, transportation benefits, 24-hour assistance services, and more.

A standout offering from Allianz is SmartBenefits, which automatically provides passengers with a fixed payment for meals or accommodations if their flight is delayed. The standard coverage for domestic routes is $100 for delays of 2 hours or more, although terms may vary. Alaska Airlines became the first airline to offer this innovative product directly to passengers.

That said, the commission model brings airlines only modest revenue buried in broader ancillary lines. Things dramatically change once a company becomes a merchant of record for tour packages instead of just providing affiliate links to partner websites.

Packages as cash multipliers

Only a small fraction of British Airways Holidays' multimillion-dollar revenue comes from affiliate commissions, with the majority derived from direct package sales. Now part of Avios Group, which manages the loyalty currency, BA Holidays operates under a merchant model. The company pre-contracts or purchases hotel inventory, bundling it with British Airways flights, baggage, transfers, and car rentals. While assuming both financial risk and customer liability, BA Holidays retains the full margin between the sale price and the underlying package cost.

Agency and merchant model in travel explained

Another illustration of how hotel resales can boost profitability comes from easyJet, the British low-cost carrier. Its dedicated easyJet Holidays division leverages the airline’s seat inventory, combining flights with accommodation, transfers, and add-ons. According to 2024 data, while a return flight generated roughly $18 in profit, a customer booking a full holiday package brought in around $98 — 5.4 times more.

Shifting from commissions to package ownership is just one strategy airlines use to grow their ancillary revenue. Below, we’ll explore a few innovative approaches.

Reinventing bundles and free perks

Unbundling services that were once included in the ticket price has drawn negative feedback: Passengers often perceive it as being charged for every small extra. In response, many airlines are focusing on rebuilding customer loyalty while maintaining their revenue streams.

Ancillary dynamic pricing

Airlines were among the first to adopt dynamic pricing, adjusting fares in response to passengers’ willingness to pay. Yet, this approach is still not widely applied to extras. Carriers that use advanced algorithms to personalize add-on prices in real time report notable gains — from a 6 percent increase in ancillary revenue per passenger at airBaltic to as much as 20 percent overall growth at an unnamed EMEA carrier using the Navitaire platform.

How flight pricing works

Ryanair, Europe’s first carrier to fly over 200 million passengers a year, has boosted growth through a data-driven pricing strategy. Using up to 20 parameters to adjust prices in real time, the airline increased revenue from hand baggage, raising its share of ancillary income from 24 to 34 percent. Likewise, Volaris applied dynamic pricing to grow add-on earnings by 8 percent. In 2024, the Mexican ULCC reached a key milestone — ancillaries now account for more than half of its total operating revenue.

Service bundles

To rebuild loyalty and add value, carriers are re-bundling ancillaries into packaged offers. Finnair, for instance, was the first to introduce a combined seat selection and in-flight WiFi package at a discounted price. Looking ahead, Finland’s flagship carrier plans to offer more bundles that include meals, carry-on baggage, lounge access, and priority boarding. The airline leverages Amadeus Nevio’s order management capabilities, which support ONE Order standards and enable modern retailing practices.

Subscription models

Among the latest innovations are subscriptions that allow frequent flyers to pay a recurring monthly or annual fee for a range of benefits. For example, Ryanair Prime offers perks such as free seat selection on 12 flights, monthly access to exclusive discounts, and travel insurance. The subscription costs approximately $105 per year, but it promises savings of over $800. With 30,000 subscribers already onboard, Ryanair aims to scale the program to 100,000.

Similarly, Avelo PLUS, from US-based low-cost carrier Avelo Airlines, provides access to exclusive low fares and discounts, free priority boarding, and the ability to share perks with up to nine additional passengers. Subscribers also receive $50 in Avelo Cash, which can be redeemed for travel-related expenses. Avelo PLUS costs $49 for the first year, with the price rising to $99 annually thereafter.

Eating for free again?

Some airlines are taking steps to regain passenger goodwill by reintroducing complimentary services, such as free meals and entertainment on Flydubai and free alcohol on Air Canada, for economy class. This move seems to be aimed at appeasing customers and addressing complaints about airlines being too profit-driven. But ditching bag fees? That’s not happening. After all, offering a few complimentary drinks is a much more cost-effective way to keep passengers happy than eliminating those hefty baggage charges.

With 25 years of experience, Liudmyla is a seasoned editor and IT journalist. Over the last five years, she has focused on travel tech, travel payments, and the advancements in NDC implementation.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.