COVID-19 has once again demonstrated the urgency of effective data exchange across health systems. To combat the disease, care providers, labs, insurance companies, public health agencies, and other players, need a unified understanding and complete picture of the outbreak. And this can hardly be achieved without standards for recording and sharing clinical information.

Healthcare data standards existed long before the current pandemic. COVID-19 has only emphasized their importance and ongoing problems. This article is too short to cover all medical data norms but long enough to provide an overview of the most critical ones. We’ll also touch upon the standard development process and main challenges related to standard adoption and usage.

Development of data standards

Data standards are created to ensure that all parties use the same language and the same approach to sharing, storing, and interpreting information. In healthcare, standards make up the backbone of interoperability — or the ability of health systems to exchange medical data regardless of domain or software provider.

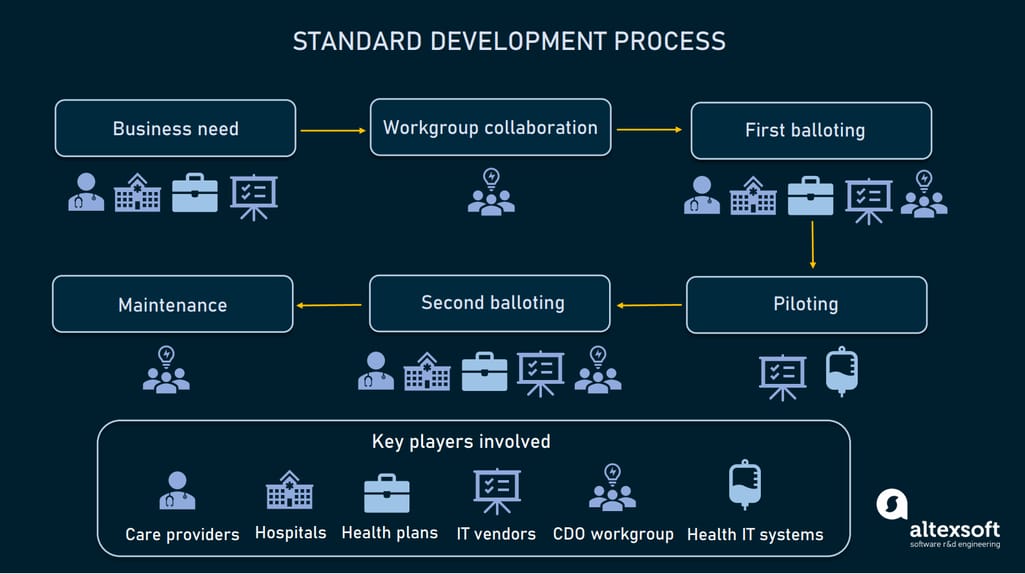

It usually takes two to three years to develop a new standard and ensure that it works properly. The entire cycle typically consists of the following steps.

How healthcare standards are developed

Identifying business needs. Stakeholders (care providers, hospitals, health plans, or software vendors) identify business needs and submit requirements for a standard to a standard development organization or SDO.

Workgroup collaboration. The task to develop a standard is assigned to a workgroup, that may include clinicians, healthcare administrators, health information professionals, software developers, and experts in regulatory requirements. The workgroup designs the standard draft along with the implementation plan.

First balloting. Stakeholders give feedback on the draft and the workgroup incorporates it into the standards. Then, all participants vote for draft standards ready for piloting.

Piloting. Healthcare systems and / or software vendors pilot the draft version of standards and provide feedback.

Second balloting. The workgroup incorporates feedback from piloting and sends the draft for the second balloting. Upon receiving comments, the workgroup makes all necessary improvements. Finally, workgroup members and stakeholders vote to approve the draft as a normative standard for use.

Implementation and maintenance. The SDO implements standards, fixes issues, and collects feedback to make improvements.

As a rule, standard development is driven by non-profit entities, and all experts engaged are volunteers who don’t receive payment for this job. The success of each standard heavily depends on the credibility of the SDO.

Key standard developers and types of standards

There are over 40 SDOs operating in the US healthcare field and accredited by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) or the International Organization of Standardization (ISO). The list of the largest and most recognized SDOs include:

- HL7 — Health Level 7 International,

- NCDPD — National Council for Prescription Drug Programs,

- IHTSDO — International Health Terminology Standards Development Organizations,

- DirectTrust Standards,

- CDISC — Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium.

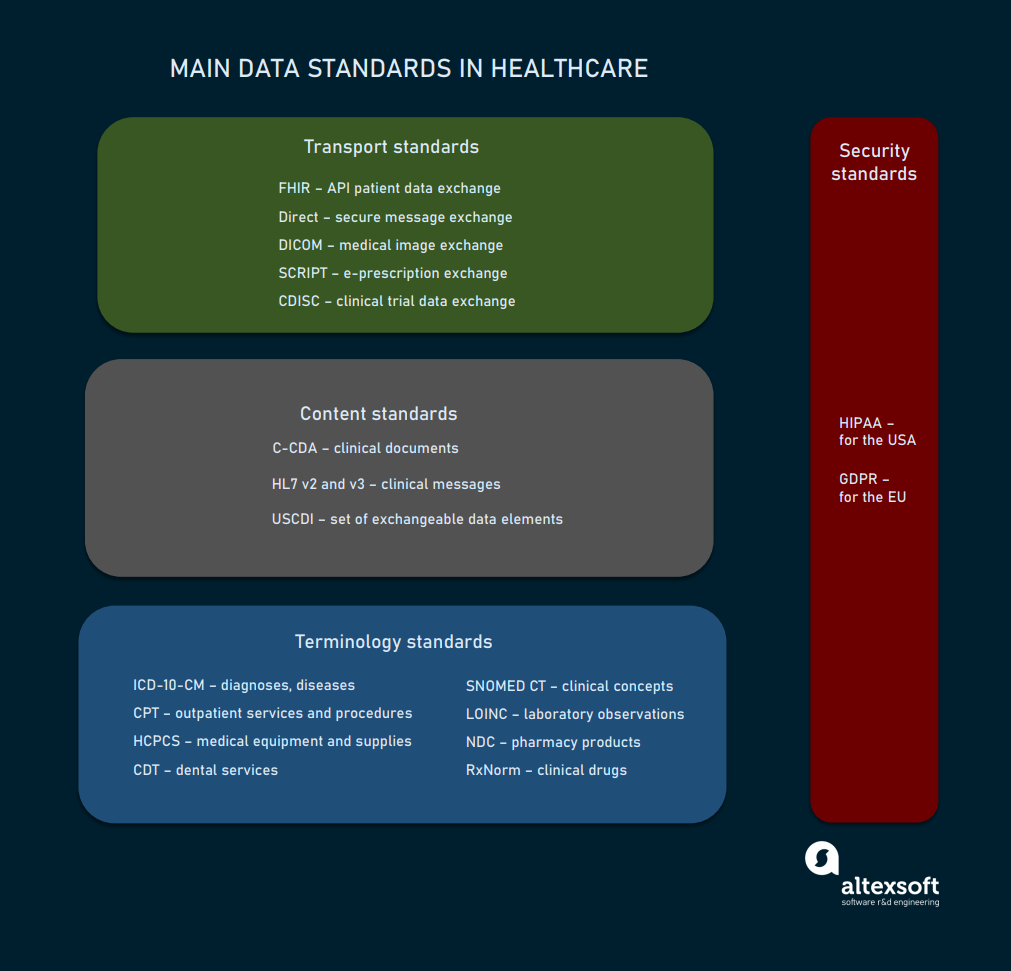

Main standards created by SDOs and widely used across healthcare organizations fall into four large groups:

- terminology standards,

- content standards,

- data exchange or transport standards, and

- privacy and security standards.

The list of key standards used in healthcare

In the next sections we’ll inspect each group of standards separately to better understand their functions, level of adoption, and how they contribute to interoperability in healthcare.

Terminology standards

Health data may be exchanged without terminology standards, but there’s no guarantee that all parties will be able to understand and use it. Imagine that each system calls the same disease or process by a different name. Or, vice versa, gives the same name to different elements. The absence of a unified vocabulary leads to miscommunication, and in healthcare it can literally be a matter of life and death.

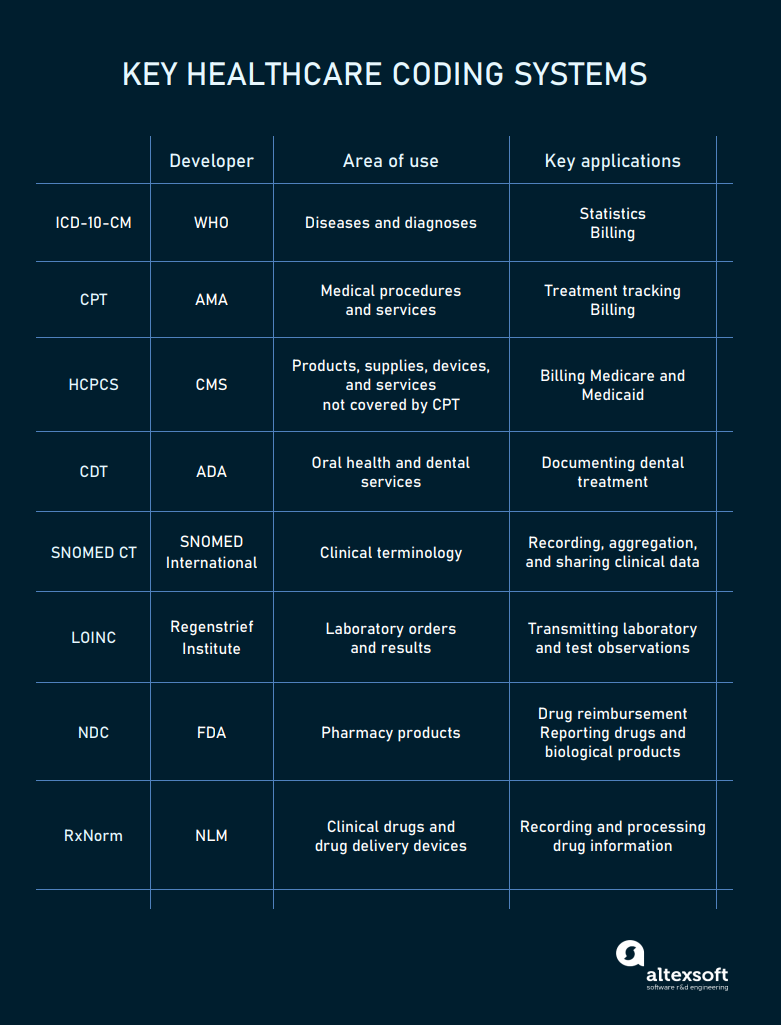

To avoid ambiguity and enhance the clarity of content, healthcare systems rely on code sets and classification systems representing health concepts.

The main codes used in healthcare

ICD-10-CM codes for diagnoses

The ICD-10, Clinical Modification (CM) is the US version of the International Classification of Diseases, created and maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO). In the United States, ICD codes are revised by the Centers for Medicare and Medical Services (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

In October 2020, the 10th revision of the code replaced the previous ICD-9-CM version. It contains over 500 updates, including new codes for vaping-related disorders and COVID-19. The number of codes in the new version amounts to 68,000.

Hospitals mainly use these codes for billing and reimbursement. Nationally and globally, the ICD serves as a universal tool to track morbidity and mortality statistics.

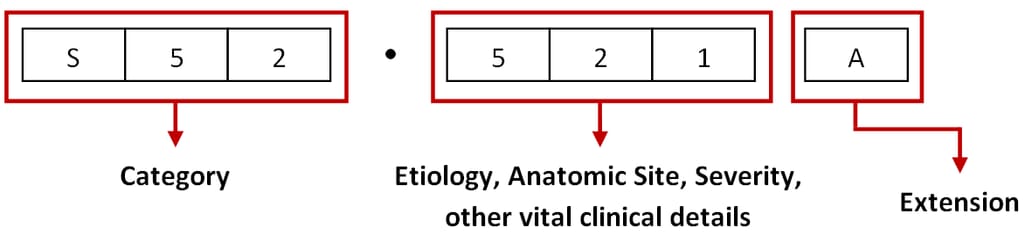

Under the ICD-10-CM, every disease or health condition is assigned a unique code three to seven characters long.

The ICD-10-CM code structure. Source: ViSolve

The first three elements represent a unique category, the second three digits describe etiology, anatomic site, severity, and other vital details, while the seventh character — or extension — specifies an episode of care for injuries, poisonings, and other conditions with external causes.

In 2022, the 11th revision of ICD codes will take effect, adding two numbers for a more detailed diagnosis.

CPT codes for medical procedures

The Current Procedure Terminology or CPT is a code system maintained by the American Medical Association (AMA). It describes outpatient services and procedures for treatment tracking and billing purposes.

Each code contains five digits or four digits and one letter and is assigned to a particular procedure. It is essential for getting payments from health plans. In a bill for reimbursement, a CPT number is paired with an ICD-10-CM code. If the service is not relevant to the diagnosis, the insurance company can reject the claim. Say, a doctor is not supposed to send a patient with stomach ulcers for a chest X-ray.

HCPCS codes for all kinds of health-related services

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System is an extended version of the CPT used to bill Medicare, Medicaid, and other health plans. HCPCS (pronounced hick-picks) has two levels.

Level 1 duplicates CPT codes and identifies services and procedures ordered or delivered by physicians.

Level 2 contains codes with one letter followed by four numbers. Supported by the CMS, it identifies services, supplies, and products not included in the CPT — like durable medical equipment, prosthetics, or drugs.

So, when are HCPCS codes used instead of CPT codes? If a service is described the same by both systems, then the CPT is valid. If there is a need to add more information, the HCPCS becomes operational.

CDT codes for dental treatment

Current Dental Terminology is developed and maintained by the American Dental Association (ADA) for electronic communication of dental services. Basically, CDT code covers oral health and plays the same role in dentistry as CPT code in general healthcare.

A CDT code always starts with “D” and has a twin in the CPT code system as many health plans don’t accept CDT codes for reimbursement.

SNOMED CT codes for clinical information

SNOMED CT stands for Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine - Clinical Terms and is owned by the IHTSDO. Recognized as a common language for medical terms in 50 countries, it enables care providers to accurately input patient data to the EHR system, aggregate information, and share it across health systems.

SNOMED CT encompasses far more concepts than ICD-10-CT. While the latter is limited to disease classification, the former covers symptoms, clinical findings, procedures, situations, substances, devices, and family history — in other words, almost any aspect related to healthcare delivery.

On the darker side, SNOMED CT is too granular to be applied for reporting. So, when it comes to billing, ICD-10-CT and CPT/HCPCS codes are used to capture a diagnosis and course of treatment and request reimbursement.

LOINC codes for lab orders and results

Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes or LOINC is a set of identifiers for laboratory tests and clinical observations. It was created by the Regenstrief Institute with HL7 interoperability standards in mind. It covers the entire scope of existing lab tests and a broad range of clinical concepts and measurements.

Backed by the American Clinical Laboratory Association (ACLA) and the College of American Pathologists, LOINC codes are widely adopted by large commercial laboratories, hospitals, research institutions, and government agencies related to healthcare.

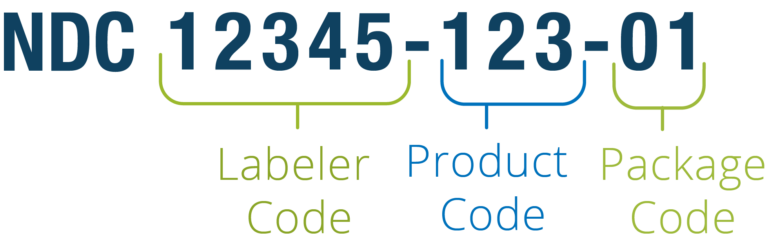

NDC codes for pharmacy products

The National Drug Code (NDC) is a unique digit identifier for human medications in the US. The coding system was created to facilitate processing of claims and drug data sharing. Currently, the codes are published on all drug packages and inserts.

The code contains three segments. The first five numbers represent a labeler (manufacturer, repackager, or distributor) and are assigned by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The next two sections — 3-digit product and 2-digit package codes — are created by the labeler.

The NDC code structure. Source: Reed Tech

For example, if a manufacturer offers a drug in packages of two different sizes, each will have its own NDC. The same medication produced by two companies will also be assigned two different identifiers. For billing, the code can be rearranged into an 11-digit string.

It may come as a surprise, but not every drug that has an NDC number was approved by the FDA.

RxNorm codes for clinical drugs

RxNorm is a catalog of all clinical drugs and drug delivery devices, available in the US. Managed by the US National Library of Medicine (NLM), it serves the purposes of interoperability, enabling clear communication between health systems, no matter the software they run.

The RxNorm code combines active ingredients, strength, and dose form. So, if these three attributes are identical, drug products will have the same identifier, regardless of brand or packaging. For example, Aspirin 325 Mg Oral Tablet has a single RxNorm ID — 211874. However, it can be marketed under dozens of different NDC codes — depending on manufacturer and package size.

Besides normalizing drug names, RxNorm links its codes to related brand-name and generic medications, as well as to other commonly used drug vocabularies.

Content standards

Content or document standards dictate the structure of electronic documents and types of data they must contain. They ensure that medical data is properly organized and represented in a clear and easy to understand form.

C-CDA for arranging clinical documents

Consolidated Clinical Document Architecture designed by HL7 is the primary framework for creating electronic clinical documents in the US. It specifies how to structure medical records and how to encode data elements for exchange.

The standard allows for capturing, storing, accessing, displaying, and transmitting both structured and unstructured information, including texts, images, and sounds. Care providers can use different C-CDA document templates satisfying various data exchange scenarios — such as the following:

- the Consultation Note template representing a response to the request of a practitioner for an opinion from another practitioner;

- the Continuity of Care Document (CCD) template to capture content that is critical to effectively continue care. This includes family history, allergies, information on recent hospital encounters. The primary purpose of the CCD document is to exchange data on a patient being transferred from one healthcare setting to another;

- the Discharge Summary template to capture information about a patient’s admission to a hospital and the continuation of care after discharge; and

- the Diagnostic Imaging Report template to convey an interpretation of image data.

C-CDA documents contain a human-readable part that can be displayed on a web browser, and a machine-readable Extensible Markup Language (XML) part intended for automated data processing.

HL7 version 2 and 3 for packaging data

A key difference between an HL7 document (C-CDA) and an HL7 message is that the former is basically an electronic representation of a physical document while the latter is a packet of data sent from one system to another.

US healthcare relies primarily on version 2 and 2.x messaging that is supported by every EHR system. Version 3 is widely adopted across the world, but not in the USA.

Each HL7 message does its specific job identified by its name that contains 3 characters. The widely-used message types are

- VXU messages to send vaccination history,

- ADT messages so send demographic updates,

- QBP messages to request immunization history, and

- RSP messages to return immunization history.

An example of an HL7 v2 message for sending demographic updates (ADT type). Source: Healthcare IT Skills

Each message is composed of several string-like segments, each starting with a 3-character name. Segments, in turn, contain fields that carry data elements.

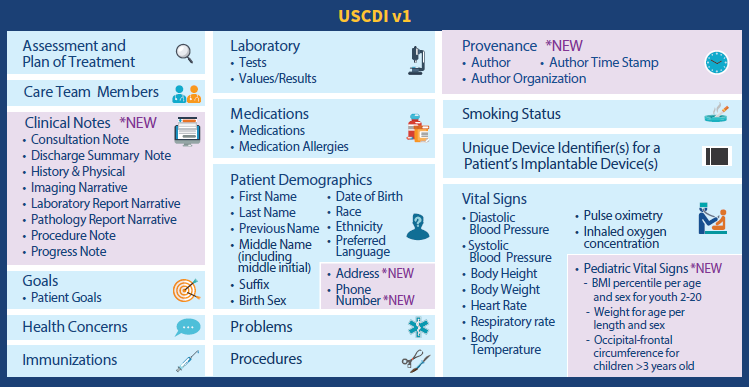

USCDI for specifying electronically available content

US Core Data for Interoperability or USCDI is not a document or messaging standard, but a mandatory set of content pieces hospitals must share on a patient’s request via APIs. The most granular parts of information — data elements — are aggregated in larger data classes like Patient Demographics, Health Concerns, Medications, Procedures, and more.

In 2020, the Office of the National Coordinator for Healthcare IT (the ONC) finalized the first version of the USCDI standard. The second release will be available for public feedback in 2021.

Electronically accessible data elements and classes specified by the 1st version of USCDI. Source: HIMSS Report

The next versions are expected to receive additional data elements and classes. But besides specifying content to be exchanged, USCDI identifies terminology systems to be used. The list of recommended code systems includes LOINC, SNOMED CT, and RxNorm.

Transport standards

Transport standards facilitate data exchange between different health systems. They define what formats, document architecture, data elements, methods, and APIs to use for achieving interoperability.

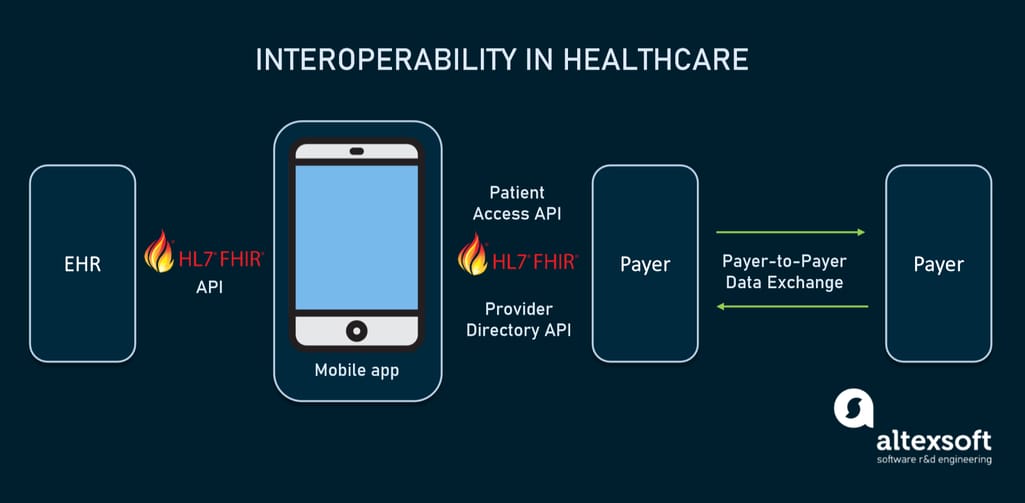

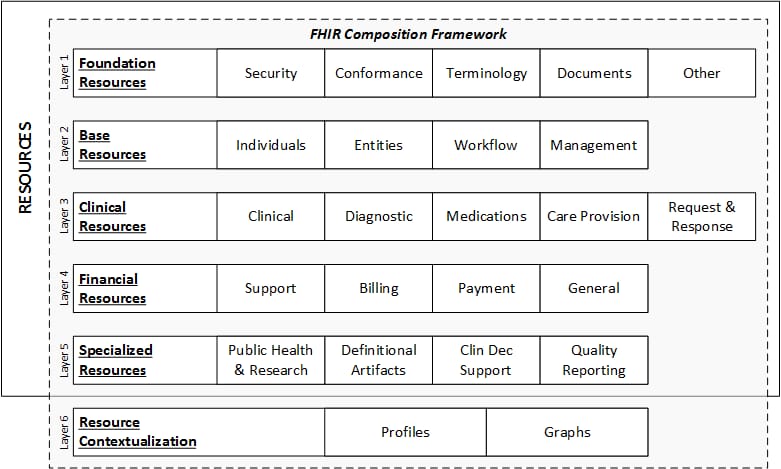

FHIR for patient access to medical records

Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources or FHIR is an HL7 standard for transmitting healthcare information electronically. The Interoperability and Patient Access final rule, issued by the CMS in 2020, requires all CMS-regulated payers to adopt version 4 of FHIR. Unlike previous releases, the fourth iteration is backward compatible so software providers can be sure that their products won’t become obsolete once a new FHIR version comes out.

The FHIR (pronounced “fire”) standard provides a set of HTTP-based RESTful APIs, enabling healthcare platforms to communicate and share data represented in XML or JSON formats. FHIR supports mobile apps that patients may download from the Apple App Store or Google Play to get their medical records and claims data.

How interoperability in healthcare will work using FHIR-based APIs

The basic exchangeable data element of FHIR is called resource. Each resource is structured the same way and contains nearly the same amount of data. Depending on its type, it provides information on patient demographics, diagnoses, medications, allergies, care plans, family history, claims, etc. Altogether, they cover the entire healthcare workflow and can be used separately or as a part of a broader document.

FHIR data layers and resources. Source: HL7 International

Each resource is assigned its unique ID and multiple stakeholders — health systems, insurers, patients, or software developers — can retrieve the underlying data element via API.

Direct for exchanging personal health information

Direct maintained by DirectTrust is a well-known technical standard in use since 2010. It is widely adopted by EHR systems across the US for the secure exchange of personal health information.

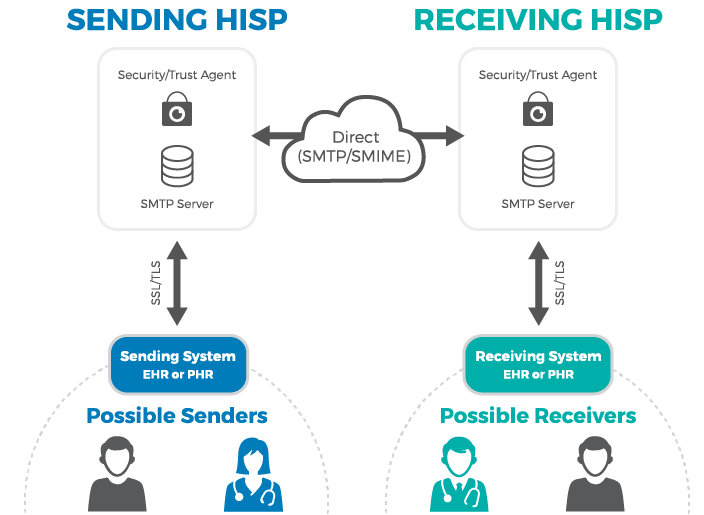

Direct messaging resembles email, but with an added layer of security. Instead of SMPT (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) servers, it employs HISPs (Health Information Service Providers) to handle data exchange. HISPs provides encryption and digital signing of each message.

How Direct messaging via HISP works. Source: MedicaSoft

Currently, over 251,000 companies have DirectTrust addresses exchanging nearly 141 million messages in three months. And this number will grow with the release of the Trusted Instant Messaging (TIM+) standard, which is already available for testing. When approved for use, it will allow all connected parties to exchange data in real-time.

DICOM for transmitting medical images

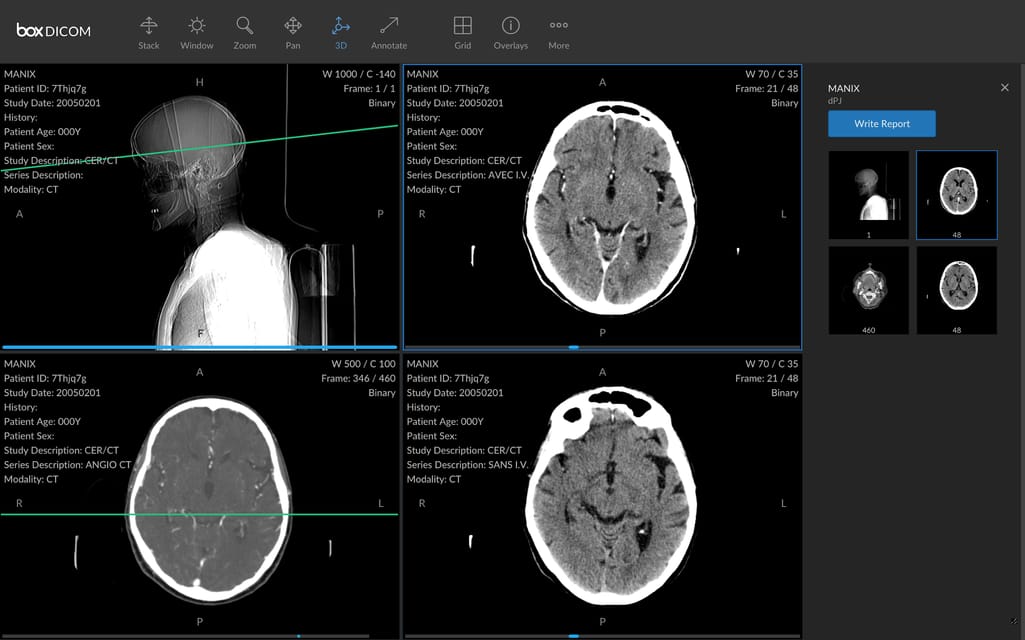

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) is an international communication protocol and file format for exchanging medical images and related data across hardware and software tools from different vendors. The tools in question include not only CT, MRI, and other scanners, but also printers, image viewers, picture archiving and communication systems (PACSs), and radiologi information systems (RISs), to name a few.

It’s important to say that widely-used image file formats — JPEG, TIFF, or BNP — tell nothing about the patient or image acquisition parameters. The standard addresses this problem, adding information necessary for diagnostic purposes. DICOM files with the .DCM extension contain a header with metadata and zero to several image pages.

A DICOM file with images and metadata. Source: HIT Consultant

SCRIPT for electronic prescribing

The Script by NCPDP is an industry standard for exchanging electronic prescriptions and related data between care providers, pharmacies, and health plans. Besides the submission of new prescriptions, it supports canceling and changing prescriptions, refilling requests, and other operations.

SCRIPT uses RxNorm codes for drug info and SNOMED codes for describing allergies. It also allows for adding a Continuity of Care Document attachment.

CDISC for medical research data exchange

Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium or CDISC standards are developed to improve the electronic exchange of clinical trial data between pharma companies and researchers. In 2016, the standards became mandatory for submitting trial data to regulatory authorities like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

To learn more, read our dedicated article on CDISC Standards.

Privacy and security standards

Privacy and security standards establish administrative and technical rules to protect sensitive health data from misuse, unauthorized access, or disclosure.

HIPAA for health data across the US

In the US, the privacy and security standards for medical information are outlined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Among other things, it formalizes the use of ICD-10-CM, CPT, HCPCS, CDT, and NDC codes in medical billing.

HIPAA Privacy Rule applies to individual medical records and other personal health information. It sets limits on the use and sharing of patient data for health plans, healthcare providers, and other players. The rule also empowers patients to freely access their medical records and request corrections to them.

HIPAA Security Rule defines what electronic health information must be protected and what technologies, policies, and procedures must be in place to ensure the appropriate level of security.

Our recent article explains how to reduce the risk of violating HIPAA rules.

GDPR for health data across the EU

In the European Union, health information falls within the scope of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). To meet the standards, healthcare organizations must

- appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO);

- conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) — or, in other words, evaluate data protection risks;

- implement a cybersecurity strategy; and

- report data breaches within 72 hours.

Similar to HIPAA standards, GDPR also gives patients the right to access their personal data.

Health data standards challenges and possible solutions to them

Obviously, the healthcare industry doesn’t lack data standards. SDOs have developed plenty of them to cover virtually every aspect of communication between disparate health systems. But the mere fact of their existence and availability doesn’t tackle all the problems related to interoperability. Below we’ll list some vexing challenges related to standards and potential ways to address them.

Medical coding speed and accuracy issues

Transformation of diagnoses, procedures, services, treatment plans, and other concepts into medical codes involves a lot of manual work, performed by specially trained professionals. Today coders rely on computer-assisted coding systems. However, the speed and accuracy of the translating process are far from perfect.

To that end, big hopes are pinned on AI-fueled software capable of identifying correct codes and suggesting them for experts to review. Currently, such intelligent systems make coding faster, however, they can’t fully replace humans and automate the entire process.

Need for mapping between codes

Each code in healthcare does its own job: SNOMED enables physicians to draw a detailed clinical picture of a patient treated, ICD-10 briefly describes diagnoses, CPT summarizes services.

That said, there are situations when translation from one code system to another is needed. For example, as we mentioned before, SNOMED can’t be used for billing purposes and must be translated to ICD-10-CT.

Standard development organizations try different options to address mapping challenges. Say, SNOMED CT runs Mapping Project Group that is working on automated methods of linking two terminologies.

Lack of compatibility between old and new standards

To comply with existing interoperability rules, hospitals must ensure the availability of content defined by USCDI through FHIR-based APIs. But let’s face the truth: Most EHR systems were built with a view to old standards. Some of them can do no more than importing and exporting HL7 v2 messages. Others mainly rely on C-CDA documents.

Neither v2 nor C-CDA fits into granular USCDI data elements or FHIR basic exchangeable data blocks — resources. So, hospitals need additional digital tools and human resources to extract data from older formats and convert them into FHIR and USCDI compatible elements. There are several initiatives to address this problem like the C-CDA on FHIR implementation guide or v2-to-FHIR project.

No two-way communication between patients and EHRs

FHIR standard allows patients to get health data via apps of their choice. However, this is a one-way street as EHRs grant read-only access to their systems. A person can request information but have no means to control and change it through the app.

Many industry experts argue that the lack of two-way communication between medical apps and EHR systems is the next biggest challenge for healthcare. And sooner or later, it will require creating new data standards.

How can stakeholders impact the situation and contribute to better communication between all parties? The answer is to actively participate in standard development processes, submit feedback, and share their ideas with the standards community.