Airline ticketing is not as simple as it may seem to passengers. It is a complex process that involves many systems, interactions, and regulations. This article aims to explain how ticketing works, what a ticket is, which accreditations an agency should have to issue tickets, and how to sell flight seats without having major certifications.

What is an airline ticket?

An airline ticket is a document granted by a carrier or travel agency to a passenger as a confirmation that a person has bought a seat on a flight. It can exist in two forms — paper and electronic (e-ticket). Today, you’ll most likely deal with a digital version, while hard copies are becoming museum artifacts.

No matter the form, the air ticket performs several important functions.

- It seals the deal between a passenger and an airline, establishing the rights and responsibilities of both parties. The ticket documents whether and under what conditions a passenger can modify an itinerary, cancel a flight, or receive a refund.

- It serves as a travel document, ensuring that an airline will provide a seat and services included in the fare for the ticket owner. On the other hand, carriers use a document as a source of information about the passenger and the booking.

- It manages relationships between multiple airlines involved in one journey (if this is the case). To be more precise, it outlines the responsibilities of the validating carrier that issued the ticket and the operating carrier or carriers that perform the flight.

Speaking of flights, conducted by several airlines, only one of them owns a ticket at any given moment. This possession makes the airline responsible for the passenger and updating their status (checked-in, boarded, flown, etc.)

Airline ticketing process

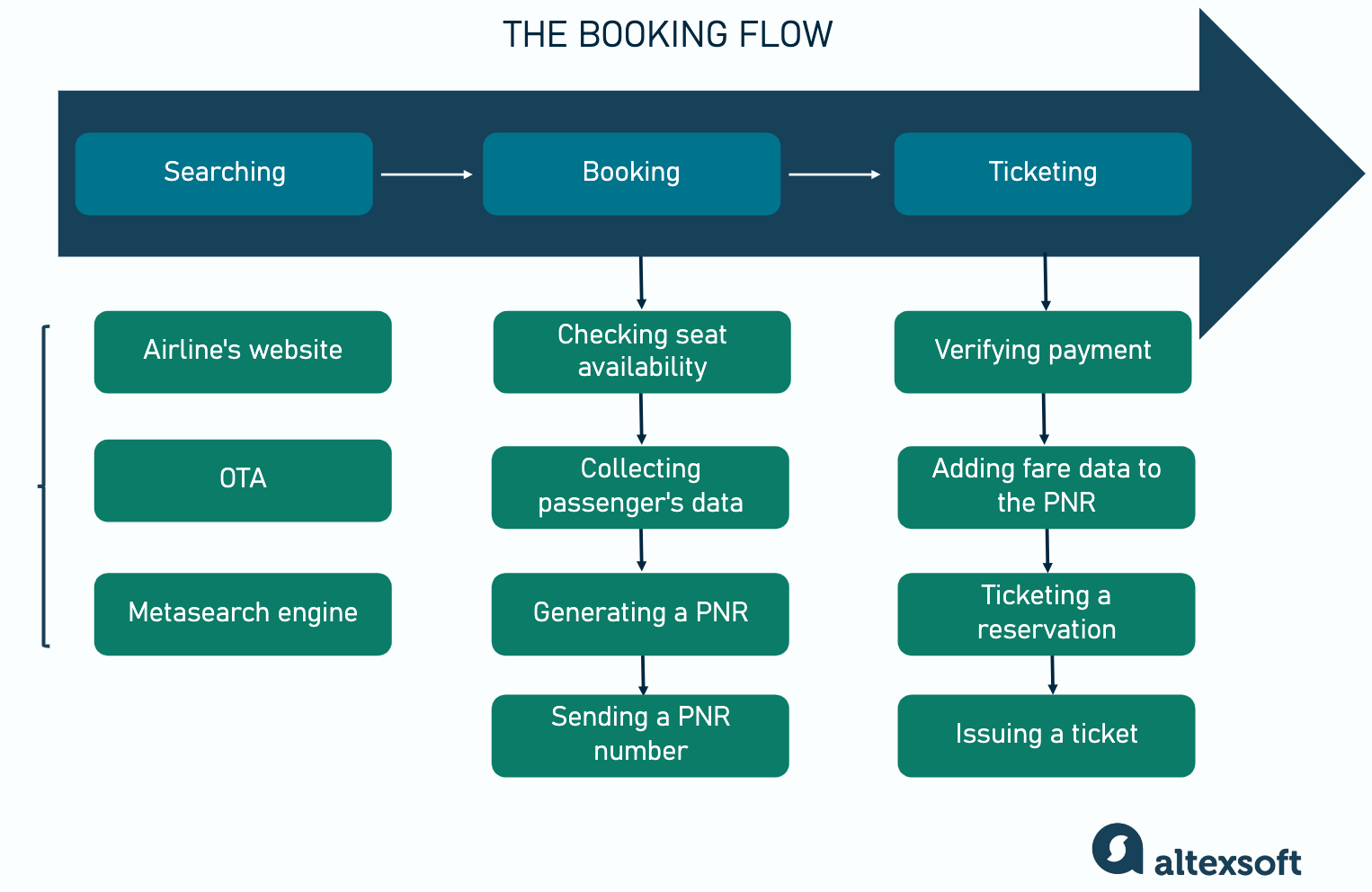

Airline ticketing is the final stage of the complex flight booking process. For a passenger who buys the flight via a website, it may seem like a single flow since everything goes so smoothly and fast. But in fact, there are three separate steps, each consisting of multiple procedures.

The booking flow

Flight search

The first step is the flight search that can happen on different platforms — airline websites, online travel agencies, or metasearch engines.

Airline web pages. When a passenger searches for a flight on an airline’s website, the query is sent directly to the carrier's central reservation system (CRS), without any third parties involved. The CRS returns the list of available options for required dates. Pretty simple and straightforward! Yet, more often than not, the choice will be limited to flights of a particular airline and its partners.

Online Travel Agencies. If you want to compare offers from numerous airlines or plan a multi-leg itinerary, Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) are what you need. They source flight data from Global Distribution Systems (GDSs), air consolidators, and partner carriers. Most OTAs rely on booking engine technology to prioritize results according to business rules and apply pricing markups before displaying airfare deals to end users.

How OTA booking engines work

Metasearch engines. Platforms like Google Flights or Skyscanner aggregate information from OTAs and airline CRSs to show the widest possible range of options, including those from low-cost carriers that typically don’t share their flights with GDSs (and consequently, with OTAs.) Yet, metasearch engines typically don’t support booking. Instead, they redirect a user to the airline website or OTA.

Flight booking

Step number two is booking. After a passenger selects a certain flight, the retailer — be it an airline website or OTA — checks with the CRS if the option is still available at the same price. Then it collects a traveler’s data to create a Passenger Name Record (PNR). This digital document contains essential information about the itinerary in question and is stored in the CRS.

PNR explained

Once a passenger has entered all mandatory details, the system generates a booking reference — a unique code that serves as an address of the PNR file in the CRS and confirms the reservation. Travelers receive such codes via email and can use them to track their flight status, change itinerary details, add ancillaries, or cancel the trip.

Ticketing

The PNR is not enough to enable ticketing. Travelers still have to seal the deal with money. For this purpose, both airlines and OTA employ payment gateways — third-party services that process electronic transactions and ensure data security. Today, in most cases, passengers pay for the flight immediately after they enter all the booking information.

Why do air prices change so often, and how is AI involved? Read about AI in airline revenue management on our blog.

Though the bank reserves the money on your credit card the moment you book a trip, it can take up to three days to verify payment details, confirm the transaction, and check if the seat is still available (yes, one more time.) That’s why there is a lag between reservation (when you receive a PNR number) and actual ticketing.

After the payment is confirmed, an airline adds the corresponding fare information to the PNR document. This specific record serves as the basis for ticket issuing.

Eventually, a passenger receives the itinerary receipt via email. This document signifies the successful purchase of an e-ticket. You can print it out multiple times or download it to any device. The airline stores the e-ticket in its reservation system.

Note, though, that the receipt doesn’t allow you to board the plane. To take your seat on the flight, you have to check in — online or at the airport — and receive a boarding pass (printed or electronic) generated by the airline’s departure control system.

Ticketing in an Interline Agreement

We already mentioned that in case of a connected flight, only one carrier owns a ticket at any given moment. But how does the process differ exactly?

In an interline itinerary, a passenger travels on multiple flights operated by different airlines that have a commercial agreement to cooperate. The ticketing process here requires synchronizing multiple carriers’ systems to create a seamless journey on a single ticket.

When a traveler selects an interline itinerary, the system must check availability and fare rules not just with one airline’s CRS but with all involved carriers – typically via a GDS. The carrier that sells the itinerary (a validating carrier) issues the ticket and is financially responsible for collecting the fare and distributing the appropriate share to partner airlines.

The PNR created will include flight segments from each airline, and it must comply with all carriers’ fare, baggage, and rebooking rules. Once the payment is processed, the GDS communicates the transaction to all participating airlines, and a single e-ticket covering the entire journey is issued.

So the ticket is issued by one airline (a validating carrier), even though others operate parts of the journey.

Ticketing in a Codeshare Flight

Codeshare flights add another layer of complexity. In this arrangement, one airline sells seats on a flight operated by another carrier.

Let’s say a passenger books a flight marketed by Airline A but operated by Airline B. The PNR is still created in Airline A’s system, but the booking must also be mirrored in Airline B’s CRS. This is done through real-time messaging protocols, often facilitated by a GDS or direct API connections.

Airline A issues the e-ticket, processes the payment, and provides the itinerary receipt. Meanwhile, Airline B’s system needs to recognize and accept the booking so it can allocate the seat and include the passenger in its departure control system.

Make sure to read our article explaining the difference between interline and codeshare flights in more detail.

Ticketing in an Intermodal Trip

Intermodal travel combines air transportation with other modes – typically rail, bus, or ferry – into a single itinerary. The goal is to enable passengers to book an entire door-to-door journey in one go. However, since different transportation providers use separate reservation and ticketing systems, issuing a single ticket across modes remains a technical and commercial challenge.

In most intermodal journeys, airlines partner with railway or bus companies through bilateral agreements or facilitated platforms like AccesRail. These platforms act as intermediaries, converting non-air segments into an airline-like format, allowing them to be distributed through GDSs using a standard airline code.

From the passenger's perspective, the booking looks like a normal multi-leg air itinerary, even though part of it is, say, a Deutsche Bahn train or a FlixBus ride. The intermodal segment is included in the PNR, and the issuing carrier generates an e-ticket that covers the entire journey.

Depending on the agreement, travelers may receive

- one e-ticket with both air and non-air segments (common with platforms like AccesRail) issued by an airline or

- separate tickets, one issued by an airline, another by a ground carrier or a platform, with reference numbers linked in the booking confirmation.

Flight booking steps and key systems

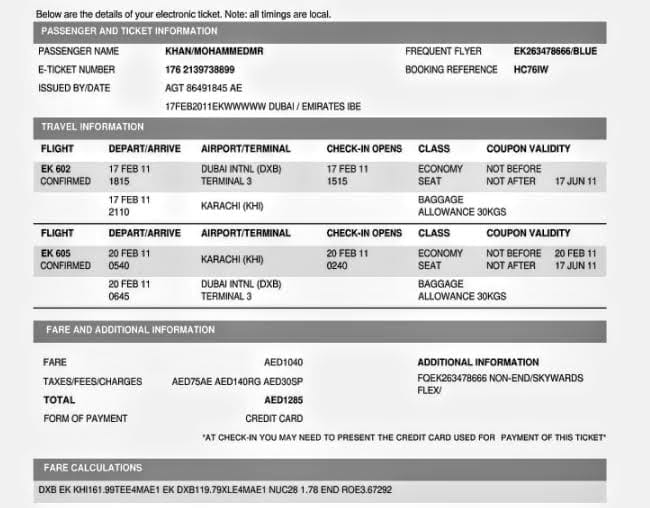

E-ticket itinerary receipt: what information it contains

The itinerary receipt contains all necessary information about the air travel allowing passengers to manage their travel, go through a check-in procedure, and just keep important details related to the journey at hand. And though the structure and design of the document vary from airline to airline, commonly the data is divided into the following logical sections.

An example of the passenger receipt. Source: Quora

Passenger and ticket information

The passenger and ticket information section shows a passenger's name, a frequent flyer code, an e-ticket number, a booking reference (PNR code), and information on who and when issued the ticket.

The 13-digit e-ticket number is a unique identifier associated with a particular passenger and flight. The first three digits are an airline code assigned by IATA. For example, 125 refers to British Airways and 176 to Emirates. The next 10 digits are a serial number.

The booking reference consists of 6 characters — letters or letters and numbers. The code is generated by a special algorithm to create a unique combination.

Both a ticker number and a booking code can be used to retrieve itinerary information, manage the booking, and check in for the flight.

Read more about IATA's codes in a dedicated post.

Travel information

The travel information section starts with a flight number — a combination of an IATA 2-letter airline identifier (for example, LH stands for Lufthansa) and a route number that can contain up to 4 digits. For instance, DL318 is a flight from Boston to Seattle, operated by Delta Air Lines.

Besides, the section covers departure and arrival times, dates, airports, and sometimes — terminals. If you see +1 near the arrival time, it means that you’ll get to the destination the next day after departure. Here, you can also find a class you are flying in and baggage allowance — or the maximum weight and size of bags permitted to check for free.

Fare and additional info

Fare and additional info section specifies fare, fees, and tax details along with a form of payment. It also gives a brief summary of the refund and cancellation policy applied to the particular ticket — whether and under what conditions you can receive reimbursement.

Main accreditations for ticketing: IATA and ARC

Ticketing is not only complex but also a highly regulated process. Airlines want to be sure that they will get paid for seats. This resulted in the emergence of large organizations handling transactions between carriers and distributors (travel agencies, travel management companies, and others). The latter must receive special accreditation to sell tickets on behalf of airlines. Globally, there are two large companies that grant such licenses — the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and the Airlines Reporting Corporation (ARC).

BSP from IATA for travel agencies outside the US

Founded in 1945 in Cuba and currently headquartered in Canada, IATA is the world’s biggest airline association, with 290 member carriers in 120 countries. Among other activities, it manages an inner payment processing system called Billing and Settlement Plan (BSP) that aggregates money from all travel sellers and distributes it across airlines. It provides a secure way to control financial operations for parties involved in ticketing.

Outside the US, only IATA-certified travel agencies can tap into BSP and issue tickets on behalf of member airlines.

Read our article about joining the BSP as well as an article on how to get IATA accreditation.

What is IATA?

ARC for US-based travel sellers

The Airlines Reporting Corporation has existed since 1985 in the US and currently includes 230 airlines and 10,700 travel agencies. Just like IATA, it mediates financial operations between agents and airlines using its own payment processor. All companies registered in the US or US territories must have ARC certificates to issue tickets for its member airlines.

Read our article to learn more about ARC accreditation options and how to get them.

The choice of accreditation for a company striving to perform ticketing will depend on whether it’s US-based or not. But commonly, large travel corporations have both ARC and IATA accreditations to verify their credibility.

Read our article to learn more about the two payment systems — ARC and IATA BSP: How they work.

Low-cost carriers ticketing

The ticketing model we’ve been describing so far refers to full-service carriers (FSC), which offer allocated seats, checked baggage, meals and drinks on board, in-flight entertainment, and other services and comforts. Most FSCs are IATA/ARC members and distribute their inventory via Global Distribution Systems. But this is very rarely the case with low-cost carriers (LCCs).

LCCs minimize flight prices by offering a bare fare without any extras, flying from secondary airports, and relying on direct online distribution rather than costly GDS mediation. But what about ticketing? Though some LCCs do sign deals with ARC/BSP, most of them avoid this type of membership, along with associated fees.

By omitting middlemen, LCCs bundle booking and ticketing in a single step. Once an airline charges a fee for the flight, it sends back a reference number that passengers can use to view and change the booking (say, add extra services or cancel the travel), check in online, and retrieve a boarding pass. So, no ticket is issued at all.

Travel agencies still have a couple of ways to book and ticket LCC flights for their clients via GDS — if regular e-ticketing is not an option.

Light ticketing model. Several LCCs offer this model via Amadeus GDS — namely,

- easyJet (UK),

- Jet2.com (UK),

- Transavia (Netherlands) owned by KLM,

- AirAsia (Malaysia),

- Spring Airlines (China), and

- Eurowings (Germany) supporting both e-ticketing and light ticketing models.

The light ticketing mimics the regular ticketing flow but excludes IATA/ARC payment mediators. Instead, the carrier withdraws money directly from a passenger’s credit card. After the airline generates a booking confirmation number, the GDS provides a travel agent with the flight information to issue an itinerary receipt and send it to the end consumer. Unlike e-tickets, light tickets are not reported to BSP/ARC.

Yet, in this scenario, no changes, cancellations, or refunds are possible via Amadeus. For all these operations, the travel agent needs to contact the airline.

Ticketless model. This option is very similar to the previous one except that a travel agent doesn’t issue any receipt. An LCC displays its inventory in the GDS, and a retailer who books it provides the passenger’s payment information and email. Once the payment is verified, the airline sends flight details directly to the passenger.

Ticketing in NDC (New Distribution Capability)

NDC, or New Distribution Capability, is a standard developed by IATA to modernize the distribution of airline products via 3rd party channels. Instead of relying on traditional GDSs, which have limited ability to handle dynamic offers and rich content, NDC allows airlines to connect directly with retailers (OTAs, TMCs, aggregators) via APIs. This gives airlines more control over pricing, content, and ancillary services.

See our handy infographic illustrating all current NDC capabilities of top 25 airlines.

In the traditional flow, GDSs store fare and availability data, generate PNRs, and facilitate ticket issuance via standardized formats like EDIFACT. But with NDC, airlines themselves handle the offer and order management through their own API-driven systems.

See our overview of all channels for airline content integration.

The process is reshaped into two core parts.

Offer management. Instead of pulling pre-filed fares from the GDS, a travel seller (like an OTA) sends an NDC request directly to the airline. The airline responds in real time with an offer that includes price, seat options, baggage, bundles, or discounts – all tailored to the request context.

Order creation and ticketing. Once the traveler accepts an offer, the airline creates an order – a record that contains all information about the flight and ancillary services. In current NDC workflows, the order still exists alongside traditional elements like PNR, e-ticket, and an electronic miscellaneous document (EMD), required for fulfillment in most airline systems.

In standard cases, payment and ticketing happen immediately upon order creation. But NDC also supports delayed ticketing – the ability to create an order without issuing a ticket or taking payment right away.

This is crucial for business travelers and travel management companies (TMCs), where the booking might need internal approval before being finalized. In this case, the seat is held, the price is guaranteed for a limited time (depending on airline policy), but the payment and ticketing are deferred until confirmation.

The order can be finalized later and the airline is instructed to process payment and issue the ticket.

Learn more about today’s challenges towards NDC transition in the industry.

Ticketing without IATA and ARC

Just like low-cost carriers, small travel agencies can hardly afford to join large associations — such as IATA or ARC. So, to ticket a booked flight, they need to cooperate with a certified organization that will tackle the problem for a reasonable fee. There are two major types of potential ticketing partners.

Airline consolidators are wholesalers that book flight inventory in bulk at discount rates and then sell it across retailers, charging a premium for each ticket. Travel agencies partnering with air consolidators can use their credentials to log in to the GDS and ticketing. Additionally, such cooperation provides agents with access to a wide range of airfares — both private and published.

Host agencies act as middlemen between travel retailers with limited resources and travel suppliers. All companies operating under the umbrella of the same host agency use the same credentials to book travel products and issue airline tickets.

Read our article to learn more about booking and ticketing for non-IATA travel agencies.

Future of ticketing

Today, one booking flow generates three separate documents — a PNR, an e-ticket, and an electronic miscellaneous record (EMR) used to collect and track information about service fees and ancillary payments. In the coming years, IATA plans to introduce ONE Order — an XML standard that will merge all those files into a single one, available under a unified reference number.

This initiative aims to simplify the booking process for travel agents, facilitate data exchange between airlines, and enhance the experience of passengers, as they will need to juggle several numbers and codes to manage their journey.

Alongside changes in airline ticketing, identity management in travel is also being transformed. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) is piloting the Digital Travel Credential (DTC) – a secure, digital version of your passport that can be stored on a smartphone.

While DTCs are primarily a border control innovation, they have the potential to dramatically improve airline ticketing and check-in processes.