“Done” doesn’t always mean the same thing to everyone. A developer might mark a story complete once all acceptance criteria are met, while QA or the product owner may still see gaps – tests unfinished, technical documentation missing, or code not yet reviewed. The confusion often comes down to mixing up two similar-sounding but very different concepts: acceptance criteria and the definition of done.

In this article, we’ll break down the differences between them, explore their roles in Agile workflows, and show how clear alignment between two approaches can keep your team efficient and in sync.

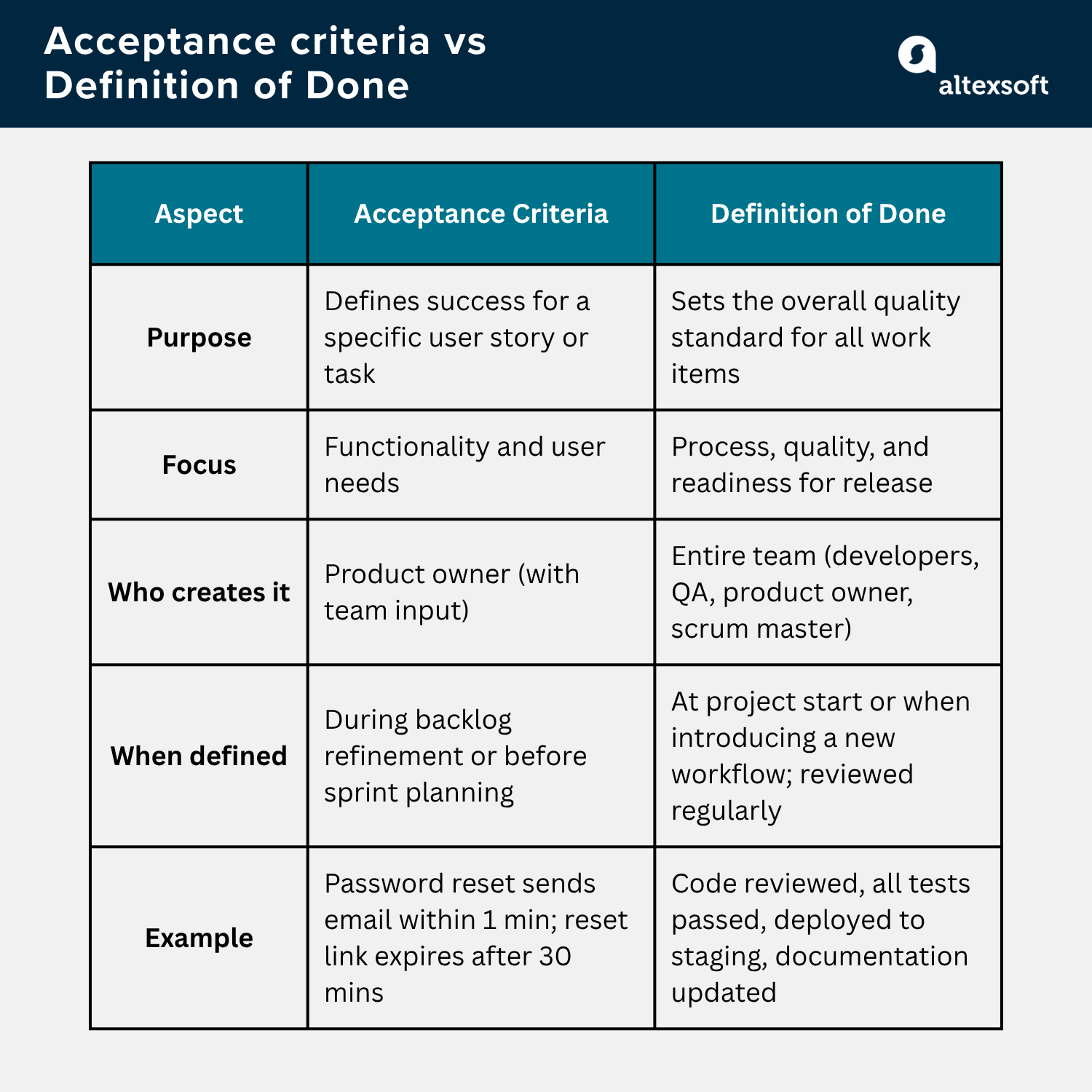

Acceptance criteria vs Definition of Done, compared

What are acceptance criteria?

Acceptance criteria (AC) are the conditions a user story or task must satisfy everyone on the team to agree it’s complete and delivers value to end users. Think of them as a shared checklist between the product owner, developers, and QA specialists – a set of rules that define what “success” looks like for a specific piece of work.

They’re written in simple, testable language so that anyone – technical or not – can understand what’s expected. Good acceptance criteria make sure the team builds exactly what the user needs, not just what they think the user needs.

Acceptance criteria are usually created by the product owner during backlog refinement or before a sprint is planned. During sprint planning, the team can review and adjust them to ensure they’re realistic, clear, and testable.

Watch our video explaining user stories and acceptance criteria

Here’s a simple example.

User story: As a user, I want to reset my password so that I can regain access to my account if I forget it.

Acceptance criteria:

- The user receives a password reset email within one minute of submitting the request.

- The reset link expires after 30 minutes.

- The user can set a new password that meets security requirements.

- After resetting, the user can log in with the new password.

Each point is clear, measurable, and easy to test. If all criteria are met, the story can confidently be marked as complete, at least from a functionality standpoint.

Well-written acceptance criteria reduce back-and-forth during testing and create a common language for everyone involved in the project. They don’t describe how to build the feature, only what must be true when it’s done right.

See a dedicated article explaining how to write acceptance criteria on our blog.

What is the definition of done (DoD)?

While acceptance criteria focus on the success of a single user story, the definition of done (DoD) defines what “complete” means for any piece of work in the project. It’s a universal quality bar set by the entire team to ensure every deliverable meets consistent standards before it’s considered truly finished.

If acceptance criteria answer “Does this feature do what it’s supposed to?”, the definition of done answers “Is this feature ready to release?”

The DoD usually includes process-oriented requirements like:

- Code has been peer-reviewed.

- Automated and manual tests have passed.

- Documentation and release notes are updated.

- The feature has been deployed to staging or production.

- All acceptance criteria for the story are met.

The definition of done is typically created collectively by the team at the start of a project or when a new product or workflow is introduced. It’s reviewed and refined regularly during retrospectives to reflect process changes or improvements.

For example, even if a “password reset” story passes its acceptance criteria, it’s not “done” until the team confirms that the code is reviewed, tested, merged, and ready for deployment according to the DoD checklist.

A clear, team-wide definition of done ensures that every increment meets the same level of quality, reliability, and readiness. In short, it’s the team’s promise that “done” really means “done-done.”

How acceptance criteria and definitions of done work together

Both acceptance criteria and the definition of done grew out of Agile’s emphasis on transparency, collaboration, and iterative delivery.

Learn more about the stages of development according to Agile methodology

In traditional project management, teams often worked toward vague or shifting goals, leading to misaligned expectations between business and development. Agile frameworks introduced short, inspectable increments, but that shift required shared understanding of what “complete” meant at every level.

That’s how acceptance criteria and the definition of done became two layers of quality control in Agile workflows – one specific, one universal. Together, they ensure that every feature works as intended and meets the team’s overall quality standards.

Here’s how they fit into the typical development flow.

- The product owner writes a user story and defines clear acceptance criteria.

- The development team uses those criteria to build the feature, ensuring each point is completed.

- Once the feature meets all acceptance criteria, it’s tested and reviewed against the definition of done – the broader checklist that applies to every deliverable.

- Only when both boxes are ticked does the story qualify as “done” and ready for release.

Let’s say the team is developing a “Save for Later” feature in an eCommerce app.

Acceptance criteria:

- Users can click a “Save for Later” button on a product page.

- Saved items appear in a dedicated section of the user’s account.

- Items can be moved back to the shopping cart with one click.

Definition of done:

- Code reviewed and merged into the main branch.

- All tests (unit, integration, UI) were completed successfully.

- The feature is documented in the release notes.

- Code is deployed to the staging environment.

Acceptance criteria confirm the what, while the definition of done confirms the quality. Together, they keep teams aligned, efficient, and confident in the quality of what they deliver.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Even experienced teams can stumble when it comes to balancing acceptance criteria and the definition of done. Here are the most common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

Confusing detailed acceptance criteria with DoD items

A common pitfall in Agile teams is mixing technical or process-oriented requirements into acceptance criteria. While acceptance criteria are meant to define what a feature must do to deliver user value, teams sometimes include items like code review, automated testing, or deployment steps – elements that belong in the definition of done.

Why is it a problem? Blurring the line between feature-specific expectations and team-wide quality principles can lead to overly complex user stories, unclear priorities, and inconsistent application of standards across the product. For instance, if a story’s acceptance criteria states “code must be peer-reviewed” alongside functional requirements like “user can reset password,” it confuses the purpose of the story and may delay development or testing.

How to avoid it:

- Ensure each criterion describes a measurable outcome the user expects. For example, “User receives a password reset email within one minute” or “Saved items appear in the user’s account.”

- Elements like code review, automated testing, documentation, or deployment readiness should be added to the team’s DoD, not to individual stories. For example, the DoD checklist might include: “All code changes reviewed by at least one team member,” “Unit and integration tests passed,” or “Feature deployed to staging environment.”

Lack of alignment on what “done” means

Another common challenge arises when different team members have different interpretations of what “done” actually means. For example, a product owner might consider a feature “done” once it’s implemented and ready to demo, focusing primarily on user-facing functionality. Meanwhile, QA might define “done” as a feature that has passed all functional, integration, and regression tests, and is fully documented and ready for release.

Why is it a problem? A story that appears complete to one role may still require additional testing or fixes, slowing down the sprint and undermining trust between the product owner, developers, and QA team.

How to avoid it:

- During backlog refinement or sprint planning, ensure that everyone understands the distinction between story-level expectations (acceptance criteria) and team-wide completion standards (DoD).

- Confirm shared understanding for each story. For instance, a “Save for Later” feature might meet all functional acceptance criteria, but it’s not truly “done” until QA verifies test coverage, documentation is updated, and the feature is deployed to staging.

- Maintain a visible checklist or reference document that specifies what “done” means for both acceptance criteria and DoD items, so all roles have a common understanding.

Updating one but not the other

Agile teams constantly adapt – introducing new testing tools, adopting updated code review practices, or refining deployment processes. However, it’s common for acceptance criteria templates or the team’s DoDs to lag behind these changes.

Why is it a problem? For example, a DoD might still specify manual testing for a process now covered by automated tests, causing redundant work or misaligned expectations between developers and QA. Similarly, acceptance criteria that reference deprecated functionality or outdated requirements can mislead the team on what truly matters for user value.

How to avoid it:

- Treat both as living documents – acceptance criteria and the DoD should evolve alongside your processes and tools.

- Incorporate discussions during sprint retrospectives or whenever workflow changes occur. Confirm that all team members understand the updates.

Understanding acceptance criteria and definitions of done: practical tips

Even when teams understand the theory behind AC and the definition of done, applying them consistently across roles can be challenging.

For product owners: Keep acceptance criteria focused on value

Product Owners are the bridge between user needs and technical delivery.

Write from the user’s perspective. Each acceptance criterion should describe what success looks like for the user, not how developers should achieve it. For example, instead of “Implement input validation,” write “Users cannot submit the form unless all required fields are filled.”

Collaborate early with the team. Discuss acceptance criteria during backlog refinement, so developers and QA can flag unclear or risky assumptions before the sprint starts.

Validate during review. Use the AC as your checklist during sprint review to confirm that the feature truly meets the user story’s intent.

For Scrum Masters: Maintain clarity and discipline

Scrum Masters ensure the team follows consistent, shared standards.

Facilitate agreement on “done.” Regularly revisit the DoD in retrospectives to ensure it still fits the team’s current practices and tools.

Guard against scope creep. When mid-sprint requests appear, remind stakeholders that new acceptance criteria mean a new story or a future refinement.

Encourage transparency. Use visual aids (like checklists on the team board) to remind everyone of the DoD and make progress visible.

For developers: Align code quality with DoD

Developers turn requirements into reality, and the DoD protects them from rework.

Use AC to drive implementation. Treat acceptance criteria as the definition of success – if code fulfills them, it’s functionally complete.

Flag inconsistencies early. If ACs contradict the DoD (for example, asking for behavior that conflicts with security standards), raise it immediately during refinement.

For QA engineers: Turn acceptance criteria into test scenarios

QA ensures that “done” actually means “done” in practice.

Derive test cases directly from AC. Each criterion should translate into one or more verifiable tests, making it easy to confirm that user stories behave as expected.

Validate against the DoD too. Beyond functional correctness, ensure that performance, documentation, and regression testing meet the team’s DoD.

Collaborate during refinement. QA input helps ensure acceptance criteria are measurable and testable – reducing ambiguity before development even begins.

Maryna is a passionate writer with a talent for simplifying complex topics for readers of all backgrounds. With 7 years of experience writing about travel technology, she is well-versed in the field. Outside of her professional writing, she enjoys reading, video games, and fashion.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.