As organizations grow, access control often turns into a patchwork of one-off permissions, inherited rights, and undocumented exceptions. Over time, it becomes unclear who can access what—and why—making audits painful and security risks harder to identify.

An access control matrix (ACM) helps address this problem at the design and governance level. In this post, we dive into what an ACM is, when you need it, and how to create one.

What is an access control matrix (ACM)?

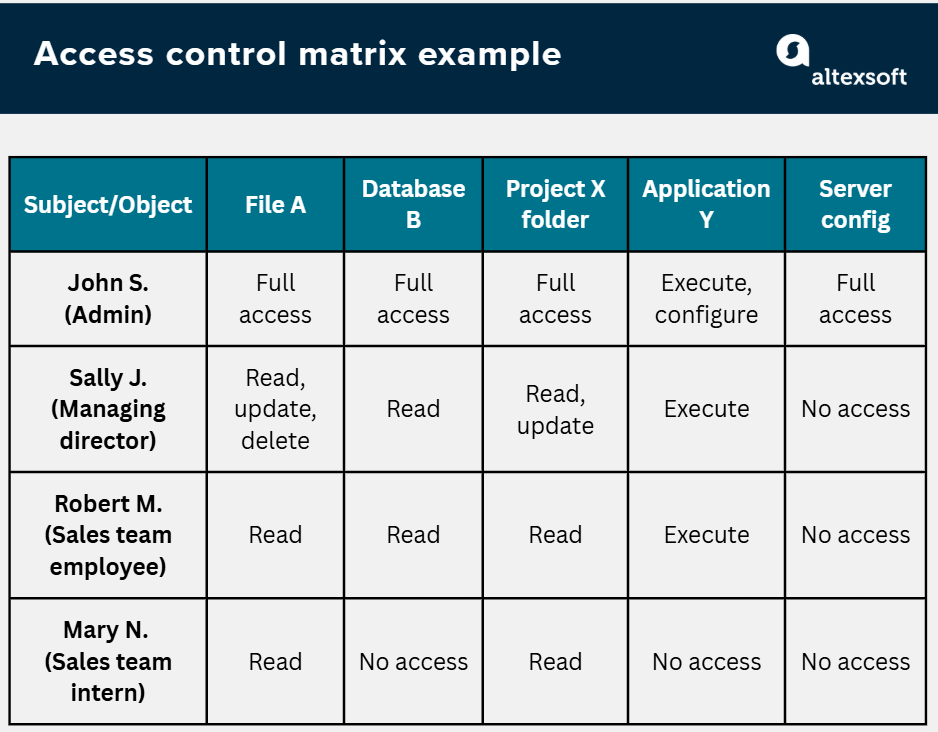

An access control matrix (ACM) is a security model that defines access rights by explicitly mapping who can perform which actions on which resources. It is typically represented as a table, where rows correspond to subjects (users or systems), columns represent objects (resources), and each cell specifies the permissions allowed.

Importantly, an ACM is almost never used as a direct runtime authorization mechanism. Instead, it serves as a design and governance tool—a way to define, validate, and document access logic before it is implemented through enforcement models (e.g., RBAC or ACLs, which we’ll explain in detail below).

Access control matrix (ACM) components

An ACM is built around three core components.

Subjects represent who or what is requesting access to a protected resource. This can include

- individuals,

- groups or teams,

- service accounts, and

- applications or APIs.

A key design decision is choosing the appropriate level of granularity. Listing every individual user rarely scales. Most effective matrices model groups or roles as subjects, reserving individual users only for exceptions.

Objects are the resources being accessed. Essentially, these are entities that need protection. Objects may include

- files, records, or databases;

- system features or modules;

- physical devices (e.g., printers, servers);

- API endpoints; and

- business entities such as invoices or bookings.

As with subjects, abstraction matters. Grouping objects into logical categories (for example, “financial reports”) instead of individual files helps prevent the matrix from becoming overly large and complex.

Permissions or access rights define what actions are allowed on each object. Common examples include

- read, write, update, delete;

- own (grant access);

- approve, export, execute;

- view metadata, etc.

Well-designed permissions align with real business actions, not just technical operations. Overly broad permissions may simplify the matrix, but they weaken security and accountability.

Access control matrix (ACM) example and template

An ACM is best understood visually. Below is a simplified example of what a matrix looks like for a small organization.

ACM example

Access control matrix (ACM) vs ACLs vs RBAC vs ABAC

As we said, an ACM is rarely enforced directly. It means that an application does not check a large matrix table every time a user clicks a button or calls an API. Instead, the ACM is used to define, think through, and validate who should be able to do what. Essentially, it serves as a reference model that is translated into concrete authorization mechanisms. How this translation is done depends on the system’s scale, complexity, and governance requirements.

Access control list (ACL)

When the matrix is sliced vertically by object (column), the result conceptually resembles an access control list.

An access control list or ACL is a list attached to a single object that defines which subjects are allowed to perform specific actions on that object.

Example:

The system stores access rules for each user directly on the object, e.g., file Invoice #4582. When User X tries to access Invoice #4582, the system

- looks at the file ACL;

- checks whether User X appears in the list; and

- verifies whether the requested action is allowed.

If User X is not listed, access is denied by default.

Pros:

This approach aligns naturally with the matrix structure and offers fine-grained control. It works well when objects have unique or highly specific access rules.

Cons:

The downside of ACL is poor manageability. While disabling a user's account effectively stops access, removing their obsolete entries from thousands of individual files to maintain a clean audit trail is labor-intensive.

Additionally, it makes audits complicated. Answering the question—"What can User A access?"—becomes challenging as the system must scan the ACL of every object in the entire database to compile the answer.

While ACLs are considered legacy for enterprise-wide user management, they remain the standard underlying mechanism for file systems (like NTFS or EXT4) and network filtering.

Role-based access control (RBAC)

Role-based access control or RBAC is the most commonly adopted access control model in enterprise environments. RBAC simplifies access management by grouping permissions into roles.

Example:

Instead of giving access to Sarah, Jake, etc., you give permissions to the "Developer" role. Since Sarah is a Developer, she inherits those permissions. If Sarah quits and Bob replaces her, you simply give Bob the "Developer" badge—no file updates required.

Pros:

The RBAC framework scales well and is easy to understand operationally. Changing a role's permissions automatically updates access for all users in that role.

Cons:

However, RBAC can struggle with edge cases and dynamic access. For example, if a user needs "Manager" access plus one specific file from another department, you might struggle to fit that into a clean role.

Attribute-based access control (ABAC)

Attribute-based access control or ABAC is the most flexible and dynamic model. Instead of static roles, it uses if/then logic based on context. Access is granted based on attributes of the user, the resource, and the environment.

Example:

Allow access IF (User = Doctor) AND (Location = Hospital) AND (Time = Shift Hours).

Pros:

ABAC is well-suited for high-security or cloud environments, where access decisions depend heavily on context. For example, it can stop a valid user from logging in from a suspicious location.

Cons:

However, it is complex to design and requires more processing power to evaluate rules in real-time.

Which one to choose?

In modern cybersecurity, you rarely choose just one framework. Most effective strategies use a hybrid approach.

Organizations often rely on RBAC as the foundation (handling the majority of standard access based on job titles), add ACL to manage exceptions, and layer ABAC on top for critical security checks (like ensuring a user is on the corporate VPN).

And the ACM remains the theoretical model that helps visualize the effective access state.

How it works in practice: technical enforcement mechanisms

Access rules are enforced through concrete technical mechanisms rather than the ACM itself. Here are common enforcement approaches.

In-line permission checks in application logic. Authorization rules are embedded directly in code (for example, if user.isAdmin). This is common in early-stage systems but becomes difficult to audit and maintain as complexity grows.

Role and permission tables managed in databases. Access is enforced by querying database tables that map users to roles and roles to permissions. This approach supports RBAC and is widely used in custom-built systems.

Object-level ACLs configured manually. Each resource maintains its own list of subjects and allowed actions. This provides fine-grained control but makes global visibility and audits harder.

Ad-hoc scripts and admin workflows. Access is granted or revoked through manual scripts, admin panels, or one-off processes. These often arise organically and are a common source of undocumented exceptions.

As systems scale, these enforcement mechanisms are typically consolidated into centralized Identity and Access Management (IAM) platforms. Even then, the ACM often remains a reference model.

How to design an access control matrix (ACM)

Designing an ACM is less about filling in a table and more about making access decisions. Here’s a step-by-step guide.

Start with business intent, not systems

Begin by understanding why access is needed, not how it is currently granted. Focus on business processes and responsibilities: who creates data, who consumes it, and who is accountable for changes. This prevents the matrix from mirroring legacy mistakes or technical shortcuts.

Define your subjects and roles

As we mentioned, listing every single employee by name will make your matrix unmanageable very quickly. Instead, if possible, group your subjects based on function, as in the RBAC model. For example, use “Junior Developer” instead of “John Doe.”

Mapping directly to individuals may be acceptable for very small systems with few users. Also, an individual-based ACM is essential to reflect highly specific needs when an employee requires a unique exception that does not fit a general role.

Also, don’t forget to include nonhuman subjects, such as system accounts, API keys, and automated scripts that also need access to your objects.

Inventory your assets and identify objects

Before you can protect your data (and assets), you must know what it is and where it lives. Create a comprehensive list of the resources that need access control.

Objects should represent meaningful resource categories, not every atomic asset. For example, grouping “customer data” or “billing records” is usually more practical than listing each table or file.

Standardize your access rights

Clearly define what each permission entails to avoid ambiguity. Stick to the basics where possible (Read, Update, Execute, Delete, etc.). Permissions must reflect real actions, rather than vague technical capabilities.

An effective ACM should be easy to review by someone who did not create it. If a third party cannot quickly understand why access exists, the design needs refinement.

If complex access rules are essential, include explanations. Clearly define complex rights and special permissions, such as "Approve" (for workflows) or "Grant" (the ability to give access to others).

Apply the Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP)

This is the most critical step. When filling in the intersection between a subject and an object, start with no access and add permissions only as strictly necessary.

Ask: “Does this role strictly need write access or is read access sufficient to do their job?”

If a user does not need access to a resource, the cell should be explicitly empty or marked “No access.”

Review and validate

Once your initial design is complete, run a “sanity check” with stakeholders. Test whether the matrix supports daily work without workarounds and whether it prevents clearly undesired access.

Check for conflicts: Are there any roles that have conflicting permissions? For example, the ability to both "Create" and "Approve" a purchase order is a separation of duties violation that poses fraud risk.

Also, simplify whenever possible. If you notice that five different roles have the exact same permissions across all objects, consider merging them into a single role to reduce complexity.

When you need an access control matrix (ACM) – and when you don’t

The value of an ACM lies in its clarity. Instead of permissions being scattered across configuration files, code, or individual system settings, the matrix provides a single, structured view of access rules. This makes it easier to reason about access, review permissions, and identify inconsistencies or excessive privileges.

ACM works well for:

Small to mid-scale systems. In smaller systems, permissions often grow organically and informally. An ACM helps teams regain control by documenting access rules in one place before complexity sets in.

High-security granularity. An ACM is especially helpful for environments where permissions vary wildly between users (e.g., "User A can read File 1 but not File 2"). In these cases, a matrix provides visibility that broad roles alone may obscure.

System design. When building a new application or restructuring a network, creating an ACM is most effective before access logic is embedded in code or configuration. It allows teams to reason about access independently of technical constraints, validate assumptions early, and avoid hard-to-reverse design mistakes.

Security audits and compliance. An ACM is particularly valuable in regulated industries that handle sensitive data, such as finance or healthcare. And if you are preparing for SOX, HIPAA, or ISO 27001 audits, an ACM (often exported as an access review report) serves as a necessary artifact to prove the "Least Privilege" control is enforced. In other words, it shows that you know exactly who has access to sensitive data.

However, an ACM is not a silver bullet. Many organizations operate successfully without a formal matrix, relying on access models and enforcement mechanisms that implicitly define access rules – without explicitly documenting them in one place.

ACM isn’t the best approach for:

Very large environments. In an organization with 10,000 users and 1,000,000 files, a literal matrix becomes massive and mostly empty (sparse). In these cases, access models like RBAC or ABAC manage permissions at scale, without designing a full-blown ACM.

Highly dynamic environments. If your users and files change every minute, maintaining a static manual matrix is impossible. Here, dynamic models like ABAC are required to make real-time decisions based on context.

Best practices for using ACM effectively

Creating an access control matrix is not a set-it-and-forget-it task. In dynamic organizations, employees change roles, projects evolve, and new threats emerge. If your matrix isn't maintained, it becomes a security liability rather than an asset.

Here are the golden rules for keeping your ACM healthy and effective.

Implement regular access reviews. "Permission creep" occurs when users accumulate access rights over time as they move between teams but never lose their old permissions.

To avoid this, schedule quarterly or annual access reviews. Force data owners to explicitly reconfirm that specific users still need access to their resources. If they don't confirm, access should be revoked automatically.

Enforce immediate deprovisioning. Automate your offboarding process. The most dangerous time for data security is the "offboarding gap"—the period between an employee leaving and their access being cut. When a user is marked as "terminated" in your HR system, their status in the ACM (and underlying RBAC/ACL systems) should instantly flip to "disabled."

Implement logging. Ensure your ACM strategy is paired with active logging. Your matrix tells you who can access data, but logs tell you who did. If a user has access to sensitive financial data, you should still be alerted if they download 500 files at 2:00 AM. Access rights do not equal blind trust.

Separation of duties. This point is worth emphasizing because of its importance. Regularly scan your matrix for toxic combinations. For example, ensure that no single subject has both the right to "Create Vendor" and "Authorize Payment." These actions must be split across different rows in your matrix to prevent fraud.

Implement IAM tools. As systems and teams scale, permissions must be enforced consistently, updated automatically, and audited continuously. At this point, organizations typically introduce Identity and Access Management (IAM) tools to enforce access through policies and provide automation, logging, and audit trails. Examples of IAM tools are

- cloud IAM platforms such as AWS IAM, Microsoft Entra ID (formerly Azure AD), or Google Cloud IAM;

- enterprise IAM solutions like Okta, Auth0, or Keycloak; and

- policy-based authorization engines such as OPA (Open Policy Agent).

Importantly, the ACM does not disappear. It remains a reference model that captures access intent and guides how roles, policies, and exceptions are defined in IAM.

Maria is a curious researcher, passionate about discovering how technologies change the world. She started her career in logistics but has dedicated the last five years to exploring travel tech, large travel businesses, and product management best practices.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.