A few years ago, AltexSoft reached a point where its existing operational methods were limiting growth. Like other companies, we struggled with setting meaningful goals that drive progress and align teams. Traditional goal-setting methods turned out to be tedious or disconnected from actual results, leading to a lack of focus and motivation.

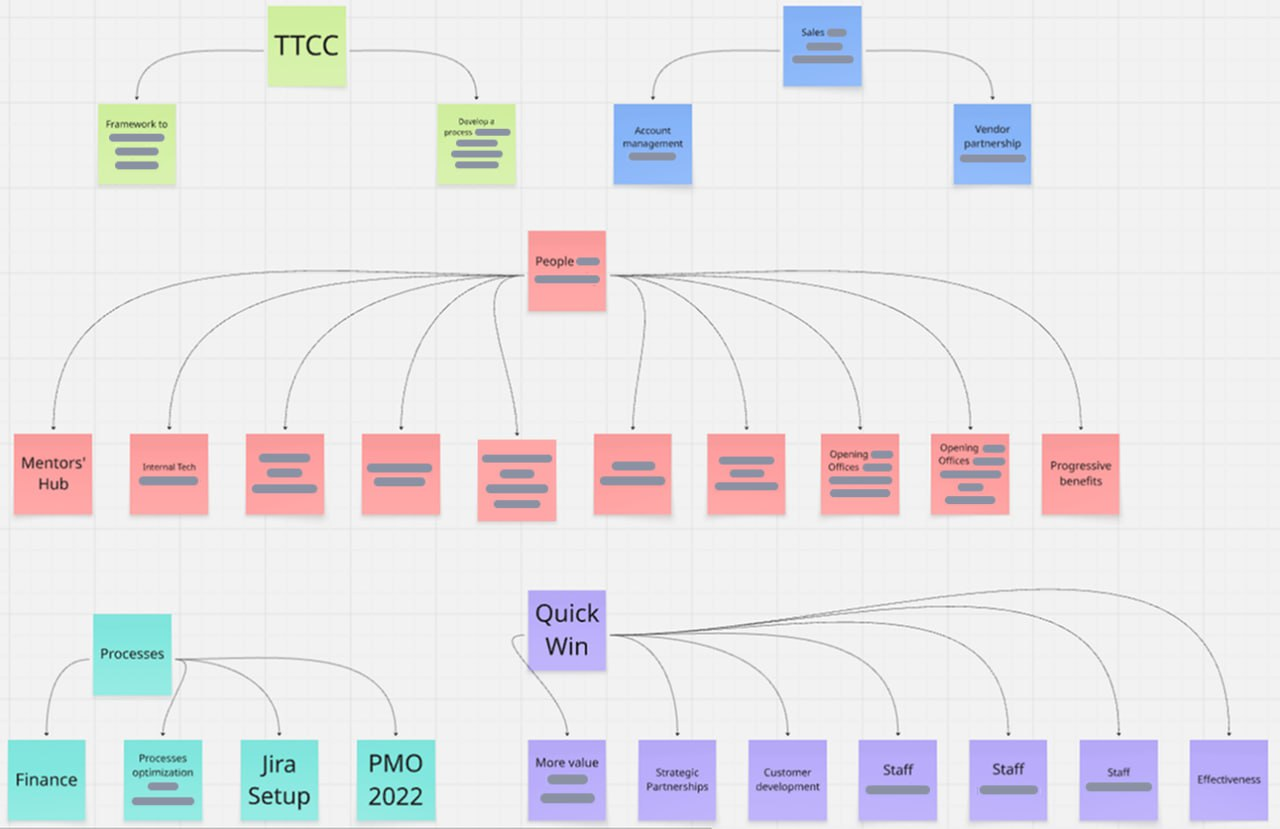

As Ihor Pavlenko, Head of Operational Excellence at AltexSoft, shared, “Previously, we held three-day strategy sessions involving top and middle management, along with external facilitators, producing 50–60 fragmented tasks per session. Many of these tasks became irrelevant before completion, and teams often worked in silos, resulting in poor alignment across the organization.”

That’s how our strategic goal-setting looked before

So we realized we have to shift from trying to optimize everything to focusing on key priorities. The main challenge lay in connecting strategy to execution.

That’s how, inspired by the example of GitLab and other big tech companies, we came to OKRs, which precisely fit our needs. We spoke to Ihor Pavlenko to learn how this framework worked for us – and we are now ready to share our experience.

What is an OKR: definition, history, types

Objectives and Key Results (OKR) is a widely used framework designed to help organizations set and track goals. Its main goal is to align company, team, and individual objectives with measurable outcomes, guiding everyone toward shared goals.

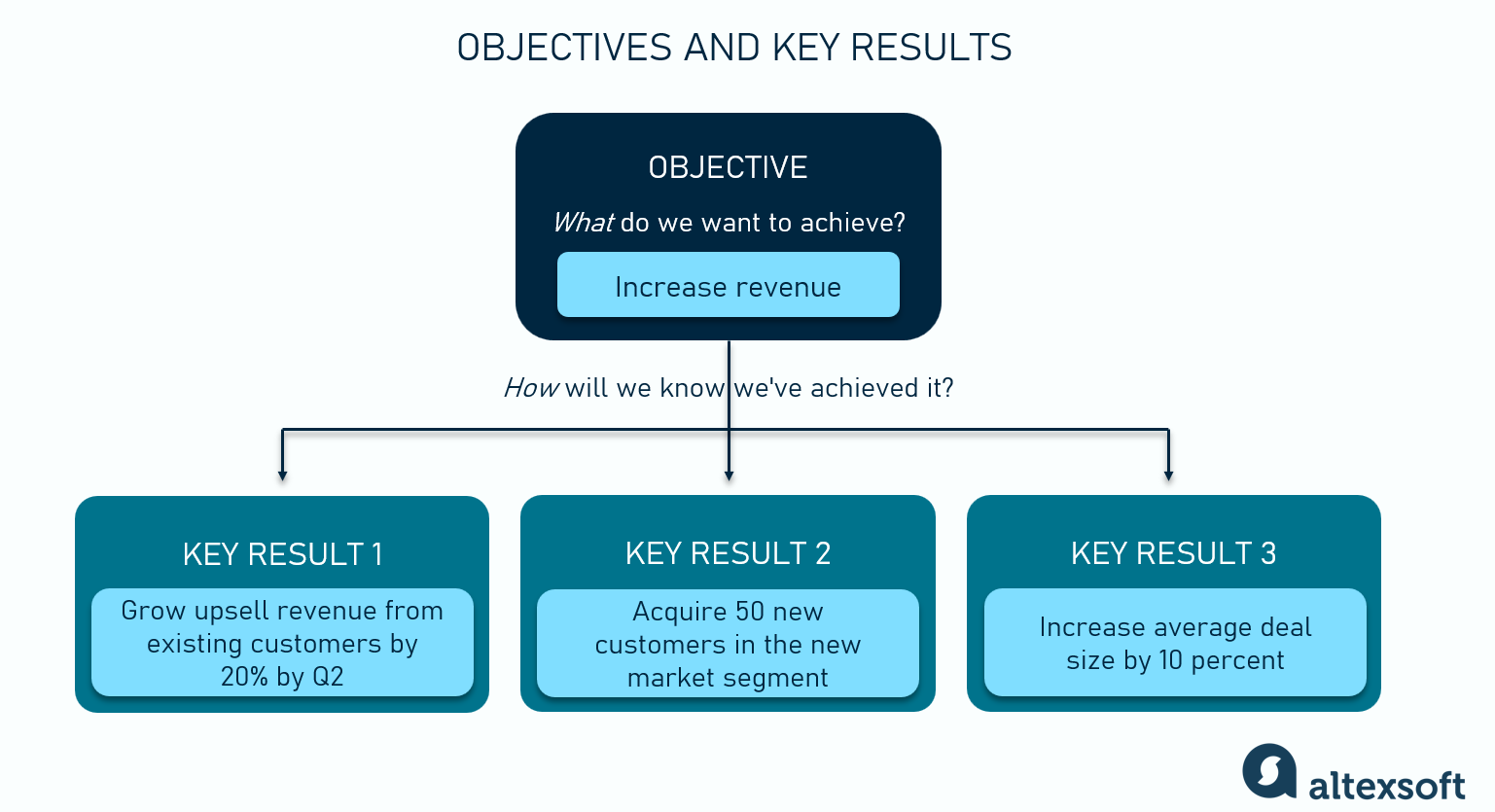

OKR example

The OKR framework includes two main components.

Objectives are qualitative goals that describe what a company, team, or individual wants to achieve. They should be clear, ambitious, and inspire action.

For example, an objective can be “Improve product quality.”

Key Results are specific, quantitative outcomes that measure progress toward the Objective, answering the question, "How will we know we've achieved it?"

For example, a Key Result can be “Reduce the number of defects by 10 percent by the end of Q1.”

Note that OKRs are not a task list or a roadmap. They don’t tell how to achieve objectives. They define the desired outcomes, while the specific actions taken to achieve them are called "initiatives."

OKRs are usually set for a defined period, such as a quarter or a year.

The OKR framework origin

The OKR framework traces its origins to the 1970s at Intel, where then-leader Andy Grove developed and implemented a system he called "Intel Management by Objectives" (iMBOs). His approach, outlined in his book High Output Management, emphasized aligning personal and team objectives with the company's overall strategy.

The concept gained widespread attention when John Doerr, a venture capitalist, introduced OKRs to Google in 1999. Doerr had learned the framework from Grove and saw its potential to help startups—which Google was at that time—set ambitious goals and track progress. Google's success using OKRs sparked further adoption.

In the foreword to John Doerr's book, Measure What Matters, Google co-founder Larry Page credited the framework for the company's success, stating, “OKRs have helped lead us to 10x growth, many times over. They’ve helped make our crazily bold mission of ‘organizing the world’s information’ perhaps even achievable. They’ve kept me and the rest of the company on time and on track when it mattered the most.”

Since then, the OKR framework has evolved and has become more flexible, with variations that suit different company sizes, goals, and industries.

It proved to work well with Agile methodologies, offering clear direction while preserving flexibility in execution. While OKRs define strategic objectives, Agile provides the framework to break these objectives into manageable tasks and continuously adapt through short cycles (Sprints).

OKR types

OKRs can be classified from several perspectives.

Committed vs aspirational OKRs. Committed OKRs – while ambitious – are expected to be fully achieved during the cycle, providing a clear target for teams to reach.

Aspirational OKRs, sometimes called “stretch goals” or “moonshots,” are intentionally bold; achieving 60-70 percent of the goal is often considered a success. Their purpose is to push teams beyond comfort zones and inspire innovation.

We at AltexSoft use both types – read on to understand the rationale behind this decision.

Top-down vs bottom-up (strategic vs. tactical) OKRs. Top-down OKRs, often called strategic OKRs, are set by leadership to define the company's high-level priorities.

In contrast, bottom-up OKRs, or tactical OKRs, are created by teams to align their work with the strategic goals.

Learning OKRs. This type focuses on skill development and gaining insights rather than specific business outcomes. Learning OKRs encourage employees to learn new skills, research, and experiment.

Personal OKRs. Personal OKRs are about self-management. Individuals can apply this framework to define and set personal goals. Some examples of such objectives can be “Run a marathon” or “Get a CILS Italian language certificate.”

OKR vs. KPI

While sometimes confused, OKRs and KPIs serve different purposes. OKRs are essentially a goal-setting framework that helps focus an organization on specific priorities. In contrast, KPIs are ongoing metrics that track operational performance and measure how well a business performs in its day-to-day activities.

Ihor Pavlenko explained that “OKRs provide direction and drive innovation, while KPIs measure the status of everyday operations.”

Importantly, OKRs and KPIs are complementary, not mutually exclusive. For example, KPIs often act as a health monitoring system for an organization, continuously tracking key metrics to ensure smooth operations. When a KPI signals a problem, it can trigger the creation of a strategic OKR to address the issue.

Say, if a company’s monthly customer churn rate (KPI) is consistently high, it may lead to an OKR aimed at improving customer loyalty and reducing churn.

OKR examples

Here are some OKR examples for various departments, including finance, marketing, sales, and operations.

Finance OKRs

Objective: Increase overall company revenue.

Key Results:

Grow upsell revenue from existing customers by 20 percent in the next quarter.

Acquire 50 new customers in the new market segment.

Increase average deal size by 10 percent.

Marketing OKRs

Objective: Become the most recognized brand in target markets.

Key Results:

Grow social media followers by 25 percent across all platforms.

Generate 500 media mentions or press coverage.

Drive a 30 percent increase in website traffic from organic search.

Sales OKRs

Objective: Drive sales growth by improving lead generation and conversion rates.

Key Results:

Increase the number of qualified leads by 30 percent.

Achieve a conversion rate of 20 percent from leads to customers.

Reduce sales cycle time by 10 percent.

Operational OKRs

Objective: Streamline internal processes to improve efficiency.

Key Results:

Reduce product delivery time by 15 percent.

Achieve a 90 percent adoption rate of the new project management tool across all teams in the first month.

Decrease operational costs by 10 percent through process automation.

The OKRs we set at AltexSoft are aligned with our strategy of rapid growth and development. They help all teams and departments focus on what matters most, get rid of less important initiatives, and come up with actionable ideas that drive the company's vision. The results speak for themselves – we consistently land on the Inc. 5000 list, so it seems we’re on the right track.

How to implement the OKR methodology

Here’s how we at AltexSoft embarked on our OKR implementation journey.

1. Lay the foundation (pre-cycle)

As Ihor shared, he started by explaining the framework and its strategic importance to the C-level management.

Plan for education. Don't expect everyone to be immediately enthusiastic about a new idea; invest time and resources in training.

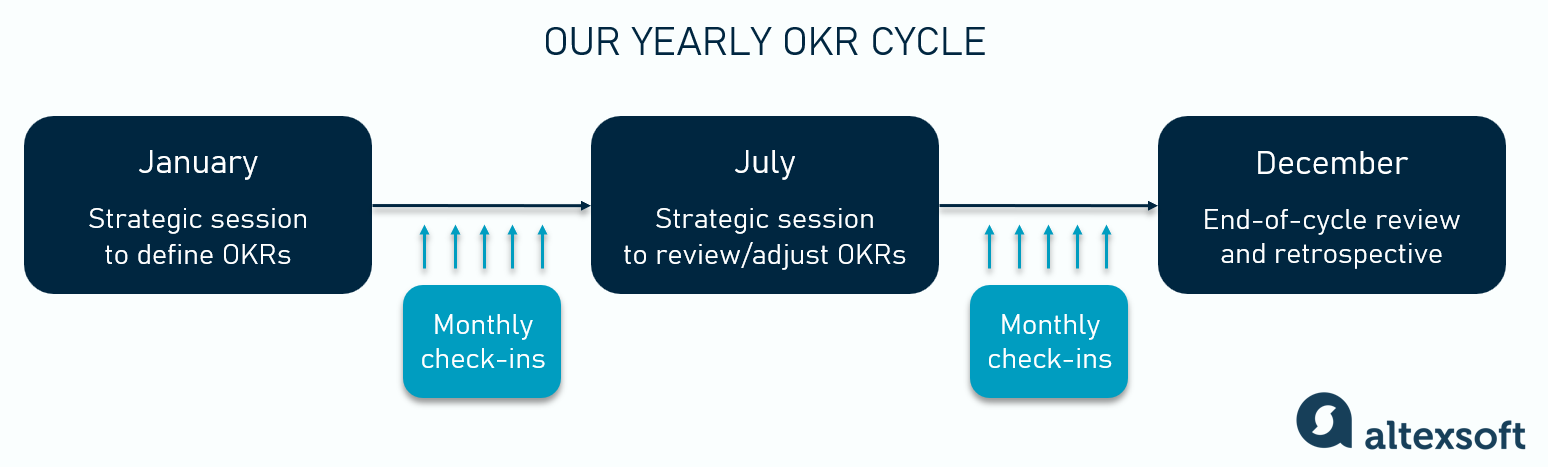

After getting C-suite approval and support, we decided on the cadence. Though most sources recommend quarterly cycles—which we initially followed—we ultimately moved to six-month periods. Since we only use OKRs for strategic goals, shorter cycles proved too time-consuming to manage effectively.

Our yearly OKR cycle

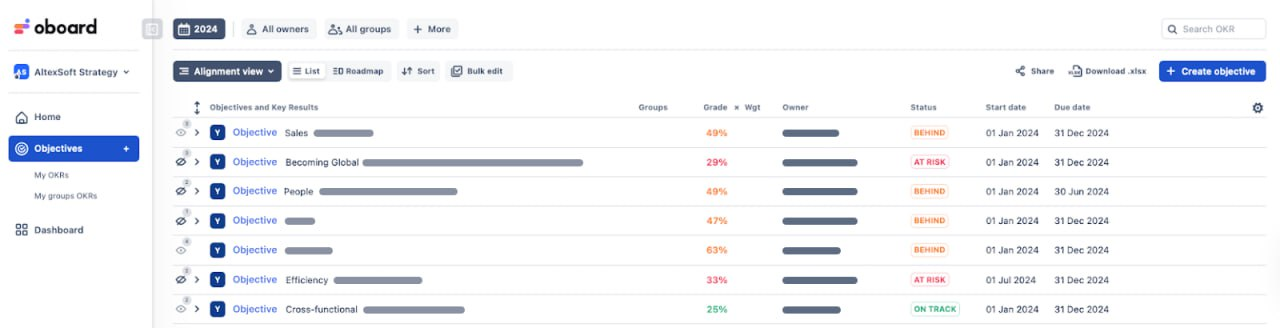

We also selected an OKR tool to manage and scale implementation. For us, it was Oboard because of its seamless integration with Jira, but there are many alternative OKR software tools you can check out (e.g., Profit.co, Tability, Weekdone, Workboard, etc.).

Some sources suggest launching a pilot program with one or two motivated teams to test the framework, identify challenges, and create success stories. However, since AltexSoft is a medium-sized company, we didn’t see the value in a multistage rollout.

2. Write OKRs (pre-cycle)

During our yearly strategic session, senior leadership sets and communicates a few high-level company OKRs that serve as the North Star for the quarter.

Our OKR examples

With the strategic context set, department leaders draft their own OKRs that contribute to the company's direction. This fosters ownership and leverages the expertise of those closest to the work.

Some companies choose to break OKRs down to the team or even the individual level. In our case, we stick to the company and the department OKRs to avoid lengthy and complex managerial processes.

A crucial part of this phase is sideways alignment, where teams proactively communicate to map out and agree upon cross-functional dependencies before the quarter begins. This prevents bottlenecks and ensures that teams that rely on each other are aligned.

3. Execute during the quarter

If you set OKRs before the cycle, begin with a kickoff meeting where leadership reiterates company goals and teams present their aligned OKRs. This creates transparency and collective commitment.

During the cycle, conduct regular check-ins – weekly for shorter cycles or monthly for longer ones. This is the "heartbeat" of the process and the primary defense against the "set it and forget it" syndrome. These brief, regular meetings are not status reports but working sessions for teams to update KR progress, assess confidence levels (On Track, At Risk), and collaboratively resolve roadblocks.

About halfway through the cycle, conduct a formal review to reassess if the OKRs are still the right ones and if any strategic adjustments are needed. This is a key mechanism for agility, allowing teams to course-correct or even stop work on goals that are no longer relevant.

4. Score and hold a retrospective

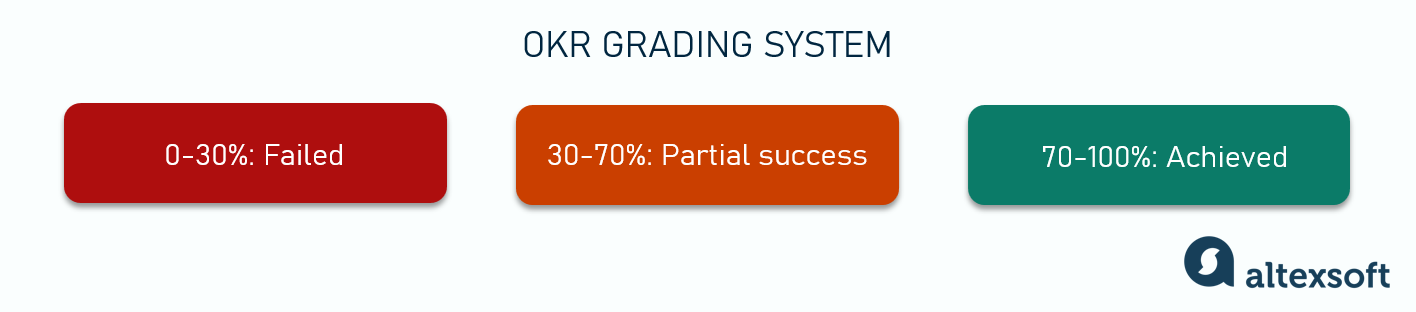

At the end of each OKR cycle, we do a thorough review to assess the successes and failures. The grading approach varies: We use percentages, but many other companies opt for the Google-suggested system.

0.0-0.3 (Red Flag). Significant progress was not made. This score signals a need to reevaluate whether the objective was poorly defined, overly ambitious, or lacked the necessary resources and support.

0.4-0.6 (Partial Success). Some progress was made, but not enough to meet the target fully. Key results were partially achieved, and the objective is still in progress. The team may have learned valuable lessons, but the objective wasn’t fully accomplished.

0.7-0.8 (Successful). The objective was largely achieved, with most key results met or exceeded. This indicates that the goals were realistic, and the team performed well in executing the strategy.

0.9-1.0 (Outstanding). The objective was fully achieved, with all key results met or surpassed. This indicates the team exceeded expectations, showing excellent execution and a strong alignment with organizational goals.

Alternatively, other companies use the traffic light system, where red, yellow, and green scores indicate failed, progressing, and achieved, respectively.

Ihor shared that we have a success rate of 60-70 percent for our highest priority OKRs. For those less critical, the rate is 50-60 percent.

OKR grading

After scoring, hold a blame-free retrospective to understand how everything went, what the challenges were, and what can be improved in the next cycle. Celebrate success when OKRs are achieved but also recognize when goals are missed.

Don’t penalize teams for missing ambitious goals; use them as learning opportunities. OKRs encourage innovation and growth, and sometimes, that means not reaching the target but learning and improving along the way.

Based on the reviews, adapt the OKRs for the next cycle.

How to write OKR: best practices

Writing effective OKRs is key to driving success. Here are some best practices and insights from our own experience.

Keep Objectives clear and inspiring

Your objectives should be short, clear, and motivating. Focus on the "why" behind the goal—what does success look like and why is it important?

As Ihor shared, early in our OKR journey, we often wrote vague objectives that people didn’t understand. By the end of the cycle, most were abandoned because no one knew how to act on them. A well-crafted objective should inspire action and rally your team around a common cause.

Example: Instead of “Become the best company ever,” write "Become the industry leader in customer satisfaction."

Make Key Results specific and measurable

Key Results are the measurable outcomes that show progress toward the objective. Ensure they are quantifiable, specific, and time bound. Each Key Result should have a clear metric to track, like a percentage increase or a set number.

Example: "Increase customer satisfaction score (NPS) from 60 to 80."

Limit the number of OKRs

Focus on a few high-priority OKRs—typically 3-5 objectives with 2-4 Key Results per objective. Too many OKRs can dilute focus and reduce impact. By keeping it simple, you ensure that teams can fully commit to achieving each goal.

Tip: Focus on the most critical areas that will drive growth, rather than every small task.

Align OKRs

Make sure OKRs don’t contradict each other. They must be mutually supportive and aligned with the high-level strategy.

Example: Planning both “Cut operating costs by 20 percent” and “Hire 10 new employees” in the same period creates a conflict, because hiring increases expenses, making it harder to achieve cost-cutting.

Focus on outcomes, not outputs

The focus should be on outcomes—the actual impact of achieving the goal—rather than just the output or the tasks completed. Make sure your Key Results reflect measurable outcomes that truly move the needle on your business goals.

Example: Instead of "Launch 5 marketing campaigns," aim for "Increase website traffic by 30 percent through targeted campaigns."

Balance committed and aspirational objectives

On one hand, objectives that are too far out of reach may lead to frustration, so some authors recommend keeping them ambitious but realistic.

On the other hand, John Doerr, a well-known OKR promoter and author of Measure What Matters, advises not to be afraid to think big: “If you’re getting 100 percent of your OKRs done, that’s not good. You probably weren’t aggressive enough. A good grade at Intel or Google would be 70 percent.”

Ihor agrees that a reasonable approach can be balancing both OKR types.

Example: Complement an achievable objective of increasing sales by 20-30 percent in the next quarter with an aspirational one of becoming the leader in your market.

Ensure alignment across teams

OKRs should align the organization from leadership to individual teams. Ensure that each team’s OKRs directly contribute to achieving company-wide goals, fostering a sense of collective purpose.

Example: If the company's OKR is "Increase revenue by 20 percent," the sales team's OKR could be "Generate $5 million in new sales.”

Additionally, team-level OKRs must also be aligned if there are any interdependencies.

Example: If the Marketing team's success depends on the Product team delivering a new feature, that commitment must be discussed, negotiated, and secured before the cycle begins.

Share OKRs across the organization

Transparency ensures everyone understands the company’s strategic goals, fostering collaboration and alignment. When everyone can see the goals, it encourages ownership and accountability.

Tip: Use specialized tools to create, manage, and share OKRs.

Regularly review and adjust OKRs

OKRs are meant to be dynamic. Regular check-ins (e.g., weekly or monthly) allow you to review progress and adjust as necessary. If something isn’t working, update the Key Results or change the approach to ensure the objective is still achievable within the time frame.

Example: If a Key Result to increase web traffic by 50 percent isn’t progressing, brainstorm new strategies to improve.

How to write good objectives

Summing up the previous section, here’s how to create effective objectives.

Ensure the objective is specific—it should describe a concrete goal, not a vague aspiration.

Make it ambitious enough to challenge the team, but still achievable within the set timeframe.

The objective should align with the company’s overall mission and strategic direction, so it contributes to broader goals.

Keep it clear, concise, and motivating—the objective should inspire your team to take ownership and drive progress.

Finally, ensure the objective is measurable so that progress can be tracked through key results.

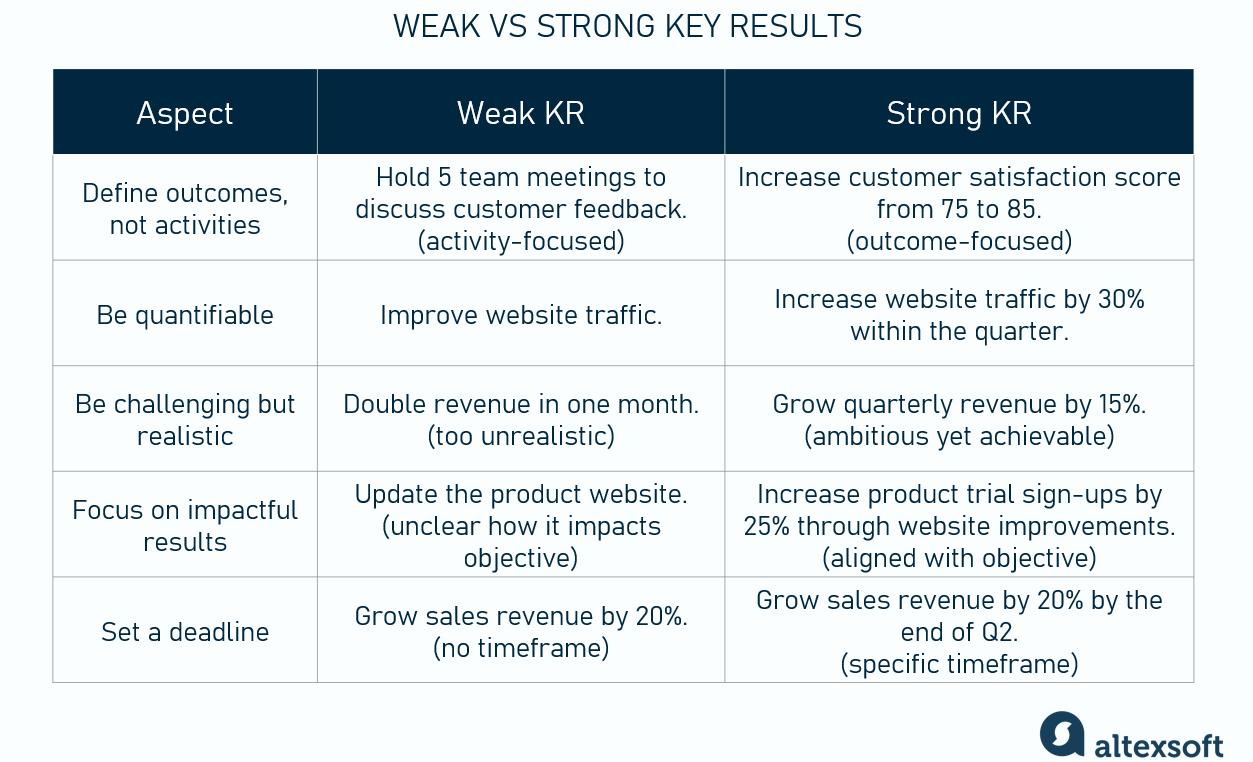

How to write good key results

Objectives are the stuff of inspiration and far horizons. Key results are more earthbound and metric driven.

To write good key results, make them specific, measurable, and time bound.

Each key result should clearly define the outcomes that indicate success, not just activities.

Use quantifiable metrics, such as percentages or numbers, to track progress.

Ensure they are challenging yet realistic, to push the team while remaining achievable.

Key results should be aligned with the objective and focus on impactful results that directly contribute to achieving the goal.

Finally, set a clear deadline to create a sense of urgency and accountability.

Weak vs strong key results

Common OKR mistakes and how to avoid them

Don't delay – OKRs bring great value, so the earlier you start, the sooner you’ll see progress.

Implementing OKRs can be a powerful tool for driving progress and aligning teams, but like any framework, it comes with its own challenges. We’ve also gone through some of them and can now share our lessons learned.

Setting too many OKRs dilutes focus. Our first OKR cycle included some 130 key results – way too many.

Expert tip: Limit to 3-5 high-priority objectives per cycle.

Sandbagging and planning business as usual means setting easily achievable targets to guarantee success, which prevents ambitious growth. The other side of the same coin is

making objectives too unrealistic, which leads to frustration.

Expert tip: Balance Committed and Aspirational OKRs. Committed goals should be challenging but achievable, while Aspirational goals explicitly signal that 70 percent completion is a success. This provides a safe framework for ambition.

Setting low-value objectives will not bring any meaningful impact on the business.

Expert tip: Every Objective must pass a simple test: "Why is this important, and why is it urgent?" The answer should clearly articulate the strategic value to the organization. If a compelling answer cannot be provided, the Objective should be discarded.

Confusing Key Results and initiatives reduces the OKR to a project plan and misses the point of measuring impact.

Expert tip: Rigorously apply the "outcome vs. output" test to every proposed Key Result. For any KR that describes an action (e.g., "Launch," "Create," "Implement"), ask the follow-up question: "And what is the desired business result of doing that?" That is the true Key Result.

For example, if you consider adding "Launch the new website," you must first ask "So what?" to identify the actual, measurable business result, such as "Increase user engagement by 15 percent."

Lack of cross-team alignment can lead to inefficiency.

Expert tip: Ensure all OKRs in your organization stem from your company’s strategy and are aligned between teams. Dedicate specific time during the planning phase for cross-team alignment meetings to explicitly discuss and commit to dependencies.

Not reviewing OKRs regularly leaves progress unchecked. It also limits flexibility and fast reactions in case of changes.

Expert tip: Hold regular check-ins to track progress and adjust if needed.

Punishing failure or tying OKR scores directly to pay, bonuses, or promotions harms the OKR system by encouraging risk-minimizing behavior, like setting easy goals (sandbagging) or avoiding ambitious moonshot goals. It can also reduce collaboration, as employees focus more on their own goals to protect their compensation.

As Ihor Pavlenko highlighted, “In contrast to the KPI-based framework, OKRs don’t imply punishment for failure or missed goals. When employees realize that, resistance drops and they’re not afraid to aim higher.”

Expert tip: OKRs should be a tool for management to guide progress, not a measure for individual evaluation. They should contribute to performance reviews but should not be the primary factor in compensation decisions.

Lack of resource commitment sets teams up for failure and fosters cynicism about the entire process.

Expert tip: Resource planning must be an explicit and integral part of the OKR commitment process. When a team presents its proposed OKRs, leaders must ask, "What resources do you need to achieve this?" and then formally commit those resources. If the resources are not available, the scope of the OKR must be adjusted accordingly.

The role of leaders in the OKR framework

Leaders must get across the why as well as the what. Their people need more than milestones for motivation. They are thirsting for meaning, to understand how their goals relate to the mission.

Leaders must be actively involved in setting, aligning, and reviewing OKRs. Their role is to support their teams, remove obstacles, and ensure that the OKRs stay relevant and ambitious throughout the cycle.

Additionally, note that OKRs work best in a culture of radical transparency and psychological safety. Radical transparency means that OKRs at all levels, from the CEO to individual contributors, should be visible to everyone in the organization, promoting accountability and trust.

Psychological safety ensures that employees feel comfortable setting ambitious goals, acknowledging when they need help, and openly discussing failures. Leaders play a key role by treating missed targets as learning opportunities, encouraging teams to take risks and be ambitious without fear of punishment.

Maria is a curious researcher, passionate about discovering how technologies change the world. She started her career in logistics but has dedicated the last five years to exploring travel tech, large travel businesses, and product management best practices.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.